The Identity Gatekeepers and the Future of Digital Identity

Updated on 7 October 2020

PI’s engagement with Yoti (a UK-based digital identity provider) resulted in improvements of the company’s privacy policy, which now includes a clearer description of how users’ personal data (including photo and passport data collected by the app) are processed.

Photo by Nadine Shaabana on Unsplash

Digital identity providers

Around the world, we are seeing the growth of digital IDs, and companies looking to offer ways for people to prove their identity online and off. The UK is no exception; indeed, the trade body for the UK tech industry is calling for the development of a “digital identity ecosystem”, with private companies providing a key role. Having a role for private companies in this sector is not necessarily a problem: after all, government control over ID is open to abuse and exploitation. But we need to ask what we want this industry to look like, and how we can build one without exploitation. These are the new digital gatekeepers to our lives.

In our response to a recent UK government consultation on digital identity, we highlighted the imperative of avoiding a future for digital identity that exploits the data of individuals. As we wrote in the response,

“It would be positive for both the UK, and the development of identity systems around the globe, if the UK builds a digital identity ecosystem that becomes a world-leader in respecting the rights of individuals and communities. Yet the risks of digital identity are large, from dangers surrounding the curtailing of people’s rights and state surveillance, to the exploitation of their data by private companies. As a result, the highest standards must be in place to meet the promise of a world-leading system.”

This is an imperative, given how these digital identity companies are becoming gatekeepers to access key services, both online and off. People increasingly either have to use their services to go about their lives, or life becomes difficult without them. Thus, they are in a powerful position. At the same time, proving your identity is something that most people don’t really want to spend a lot of time thinking about. This is a powerful combination that leaves opportunities for abuse.

As we imagine what the future will look like for digital ID, we don't want to see one in which companies in the digital ID industry are able to exploit our trust and take advantage of their position in the market. The burgeoning digital ID industry deserves our attention, and potential abuses must be brought to light.

It is essential that we question how this industry should behave. One of the behaviours to query, as we've seen in other sectors, is businesses using your data for other purposes.

Using your data for other things: the example of Yoti

An example of this is the UK-based digital identity provider, Yoti. Since the introduction of the Yoti app in 2017 it had been downloaded 3.7 million times by May 2019. According to Yoti this figure is now over 5 million.

Operating through its app, if a user chooses, they can add an ID document. Yoti specify these as “Government-issued or other official identity documents (for example, passport, driving licence)”. Yoti makes use of the government-issued ID document to provide verified identity for its users.

Users can also take a ‘selfie’ of themselves for the purpose of having a photo on the account. This photo can be “shared as part of proving your identity.”

Yoti states the purpose of their biometric identity app is to “provide you with a quick, easy, secure and privacy-friendly way to prove your age and / or identity, online and in person”. If an organisation accepts Yoti, then you can share details that have been verified by Yoti and taken from the ID documents you have uploaded to the Yoti app. The app includes welcome features, like the ability to only share particular attributes – for example, the ability to only share the fact that the user is ‘over 18’, rather than sharing all the information on their ID.

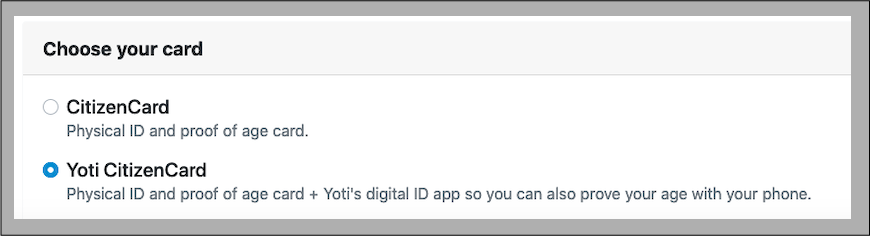

Yoti is used not only by private businesses, but also the States of Jersey (Government of Jersey); the Improvement Service (for local government) in Scotland; and the Yoti Citizen Card option is a pre-ticked option when applying for CitizenCard proof of age cards. Yoti also works globally, with an office in India and user experience research in Africa.

The concept behind the core Yoti offering is not unproblematic. Big Brother Watch has criticised Yoti’s part in a growing “casual use of biometric checks”. Privacy International has critiqued the extent to which identification systems can truly capture a complex, changing, essential thing like ‘identity’, resulting in discrimination; concerns echoed by researcher Zara Rahman. While Yoti is keen to emphasise the work they are doing on issues surrounding inclusion, and are aware of some of the complexities, the fact remains that the credentials that are valid in the current Yoti app are based largely on state ID documents. Privacy International’s research has shown that identification requirements are a major source of exclusion for those who lack access to identification.

But we must also ask what Yoti is doing with the data they obtain from users of their app. This includes data from government issued identity documents, like passports: the ‘gold-standard’ for an identity credential. Similarly, they have data including the image of a person’s face (‘the selfie’), verified to be theirs against that same document.

That they get these sources of data from users places them in a privileged position compared to many other apps. What they do with this, besides their core offering of identity and attribute verification, needs a closer look.

Yoti Age Scan

In April 2019, Yoti launched a new initiative, and potential income stream for the company: Yoti Age Scan technology. This product - described by Yoti as “using Artificial Intelligence (AI) for good” - estimates an individual’s age based on their image. This is used, for example, within the Yoti app for those who have not uploaded a verified ID document that contains their age; at self-service checkouts to see if an individual is old enough to buy alcohol; to access social media services aimed at teenagers; or to access adult content online. Yoti charge businesses to estimate the age of a face.

In the case of the use of Yoti outside of the app, a photo of the individual is analysed by Yoti with no other identifying information, and the algorithm decides whether this person is over a certain age threshold. The photo of the individual is deleted and not further stored.

But how did Yoti train its algorithm? As outlined in Yoti’s white paper on the Age Scan, data to train their algorithm is from three sources: data from Yoti users, from the APPA-Real database which Yoti state is a “public domain source”, and from volunteer data collection activities in Kenya and according to Yoti also in the UK.

In relation to data from Yoti users, if you have downloaded the Yoti app, at the point you add your verified identity document and it is accepted, your data becomes part of the training dataset. Specifically, this includes the year of birth and gender taken from your verified identity document; your ‘selfie’ photo taken when you set up the account; and Yoti researchers add other tags/ attributes for example by tagging skin colour.

As of July 2019, Yoti had data of over 72,000 users that they were using to build and test their model. Yoti have told us that this data is held on a separate R&D server, where it is not stored with data like the name of the user.

Privacy International have engaged with Yoti and raised concerns about Yoti’s actions when we met in person. This includes:

- At the point an individual has a verified ID document on their Yoti account, they are added to the training dataset. Yet once you have a verified ID document linked to the Yoti App, not only would you have no need to use Age Scan within the App, there are a vanishingly small number of scenarios when you would need to use Age Scan to prove your age when buying age restricted goods. This is because you can simply show the retailer your verified age in the App.

Yoti refute that there are a vanishingly small number of scenarios when you would need to use Age Scan if you have the App. For instance, an individual might wish to buy age-restricted goods at a self-service checkout without taking out their phone or if they do not have their phone on them.

- At the time that Privacy International spoke to Yoti, in Privacy International’s view their July 2019 Privacy Policy lacked transparency as to the use of Yoti user’s data for the purposes of age verification, and the quality of information provided was poor. There was little clarity as to how the users’ data was used as part of the Age Scan dataset.

Privacy International’s concerns were based on a detailed review of Yoti’s Privacy Policy, as well as our experience of signing up to the app and going through the ‘on-boarding process’. Yoti have made improvements to their Privacy Policy following our conversation.

- In Privacy International’s opinion, in adding Yoti users’ data to a training dataset used to train age verification technology, Yoti were using their customers' data in a way they would not reasonably expect and for a purpose other than which they provided it, raising questions as to the fairness of this use and the principle of purpose limitation, both of which are core tenants of data protection.

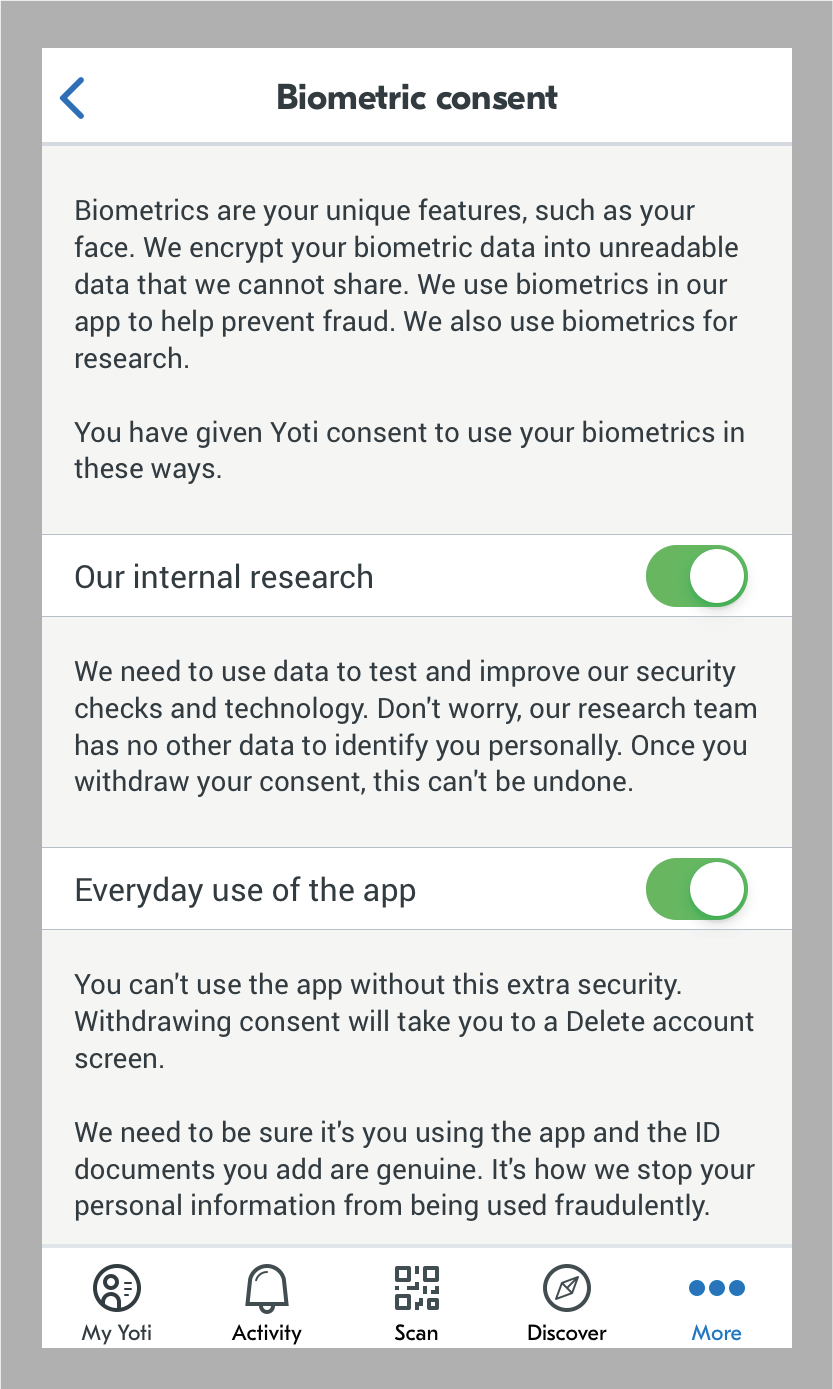

- When we first approached Yoti, there was no accessible way for Yoti users to opt out of use of their data in the training dataset and no accessible way for Yoti App users to request that their data is deleted from the training set without stopping them being able to use the app altogether. Yoti have subsequently introduced an opt-out for “Our internal research” of biometric data. As they state on the options screen, “We need to use data to test our security checks and technology. Don’t worry, our research team has no other data to identify you personally. Once you withdraw your consent, this can’t be undone.” Of course, apart from your photograph, Yoti do have access to ‘other data’ that they use for Yoti Age Scan: the year of birth from your passport.

- This opt-out is buried deep in Yoti’s setting menu, and is far from obvious. Whilst user’s are notified of this during onboarding*: "You can withdraw your consent at any time by going to More>Settings>Account Settings>My Data>Biometric Consent," it is notable that users are not notified at onboarding of this evidence from the Privacy Policy:

“Please note that if your data has already been used to train or develop a model or machine learning algorithm, it is not possible to extract your data from that model.”

Essentially, it is not made clear that a user may have data from their documents used to train the algorithm unless they opt-out prior to uploading documents to the app. We believe that an opt-in would be a far better solution.

Since talking to Privacy International, Yoti have made welcome improvements to their privacy policy, which have gone some way to making it some degree clearer the use to which they’re putting a user’s photo and passport data.

We would encourage Yoti to actively communicate to customers whose data formed part of the training dataset to ensure they are aware of how their data has been used. We do not believe that the more than 70,000 users whose data has been used to train the algorithm were adequately informed about the use of their photographs and data from their passport or other identity document. Yoti have informed us they have no way to contact their users to do this. However, even so, Yoti could take steps to reach out to their users: through a notice on the app, public communication, and notices at the places where people use Yoti.

Yoti have replied at length to this piece [see below]. In addition to feedback on this piece, Privacy International sought further clarification on a number of points, to which Yoti also replied. One such point, was Yoti’s reliance on ‘legitimate interests’ justification for use of data in the dataset. Yoti were not forthcoming with a copy of their legitimate interests’ assessment, on the basis that this was an internal company-confidential document. Whilst we acknowledge that there may be a justification for not publishing such assessments in full, we would encourage companies, including Yoti to lead the way in publishing legitimate interest assessments, or at least a summary.

This approach mirrors the Article 29 Working Party Guidance, endorsed by EDPB, on data protection impact assessments which states

“...controllers should consider publishing at least parts, such as a summary or conclusion of their DPIA. The purpose of such a process would be to foster trust in the controller’s processing operations and demonstrate accountability and transparency. It is particularly good practice to publish a DPIA where members of the public are affected by the processing operation.”

Further, the Article 29 Working Party Guidelines on Transparency, endorsed by the EDPB, state in relation to 'legitimate interest':

"As a matter of best practice, the controller can also provide the data subject with the information from the balancing test, which must be carried out to allow reliance on Article 6.1(f) as a lawful basis for processing, in advance of any collection of data subjects' personal data...In any case, the WP29 position is that information to the data subject should make it clear that they can obtain information on the balancing test upon request. This is essential for effective transparency where data subjects have doubts as to whether the balancing test has been carried out fairly..."

Yoti Age Scan is just one example of digital identity. The issues outlined above can be used to reflect on wider issues relating to the use of data gathered in the course of identity services: how do we want the identity industry to treat our data? What is the future for this market, and how do we limit what these companies are doing with the data they gather in the course of their operations?

The future of digital identity

As we look towards the future of a digital identity market, we cannot allow it to develop into one where players profit from the exploitation of the data of its users. If we see a situation where digital identity companies are earning their keep from the use of data outside of the core provision of identity, then we risk both the public trust and a distortion of the market. These distortions will lead to activities not to the benefit of the user, but one in which the user is a mere product.

EDITED TO ADD 21/10:

*There is a reference to the R&D opt out on the biometrics screen at onboarding.