The legacy of demonetisation: how India’s cashless future threatens to erode citizens' privacy

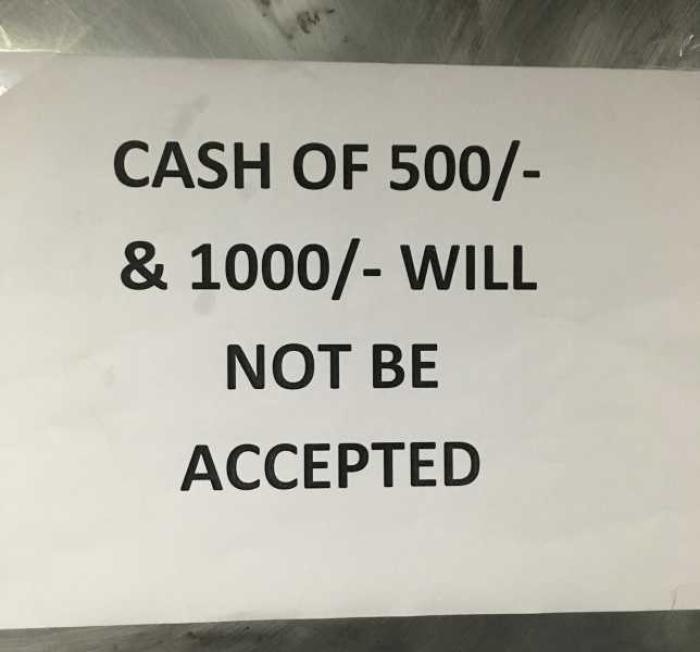

The move to digital payments, without an adequate legal framework, is a double-blow to privacy. India is proving to be the case study of how not to do the move to the cashless society. We are seeing in India the deeper drives to digital: linking financial transactions to identity. On the 8th November, Prime Minister Modi of India announced that 500 and 1,000 rupee notes – 86% of the money supply – would be removed from circulation. The initial justification for this was to tackle the proceeds of corruption: the measure was initially described by a minister as a “surgical strike” against black money in the economy.

Whether you’re in agreement with Modi’s motives or not, you have to agree that the impact of this measure was far from precise. Even for those least affected, queues outside of banks for changing money or withdrawals last for hours. It’s the hardest on the elderly and the sick – there are claims that over 100 people have died due to demonetisation. There are reports than one woman gave birth while in the bank queue. A woman set herself on fire after trying for three days to change the old 500 rupee notes that were the only money her family had.

Reports from the cities are harrowing enough, yet reports from rural areas are even worse: even in those villages lucky enough to have a bank, rural branches have been slow to receive cash. Rural prices have collapsed, workers have gone weeks without pay. Women looking to build a safety net, away from their husband’s knowledge, have seen years of savings suddenly become worthless. No matter whether they still support Modi’s decision or not, for many people the experience of demonetisation has been brutal.

The motives for demonetisation will continue to be debated at length. The discourse is not only the fight against “black money” towards Modi’s long-held goal of achieving a cashless society. Prior to demonetisation, Modi made clear his desire of achieving a cashless society in India, through what is referred to as the JAM trinity. This acronym refers to the accessible and poor-focused Jan Dhan bank accounts; the Aadhaar biometric identity scheme that has already enrolled over a billion people; and mobile, referring to apps and mobile Internet. After demonetisation, Modi emphasised his goal to move towards a less-cash, and eventually a cashless, society. Demonetisation, as Modi put it, “is the chance for you to enter the digital world”.

A problem with this position is that cash is not the burden to a modern, digital economy that its enemies describe. For example, a belief that cash is holding back eCommerce in India is mistaken. Prior to demonetisation, businesses running online services in India adapted to the prevalence of cash in the economy: Uber in India enables cash payments, online retailers have Cash on Delivery as an option. This approach has borne fruit for those in the eCommerce sector. A recent report by The Fletcher School on the digital future of commerce around the world found that, far from stifling the sector, the prevalence of cash in economies including India, Indonesia and Colombia still enables a fast rate of innovation in eCommerce.

Despite this, as the demonetisation shows, the push for the cashless society continues. Demonetisation is not going to be the last move towards eliminating cash from the economy. A government think-tank has suggested increasing the cost of cash transactions. The “war on cash” is far from over.

This move towards cashless society is being made without the necessary safeguards being put in place to regulate such a system and to protect citizens and their data. When we use cashless payments, we are potentially giving the payment processor a large amount of our data: not only where we’re buying, but from who, where and when. Further to that, think what can be learnt through an analysis of our spending: the shops we shop in, and what we buy and when. It gives a clue to our religion, where we spend our time – and even our worldview. Without the necessary data protection and other sectorial regulations, and the enforcement of those regulations, this leaves us open to exploitation. In the India, the lack of these regulations is combined with a model that is looking to monetise this data.

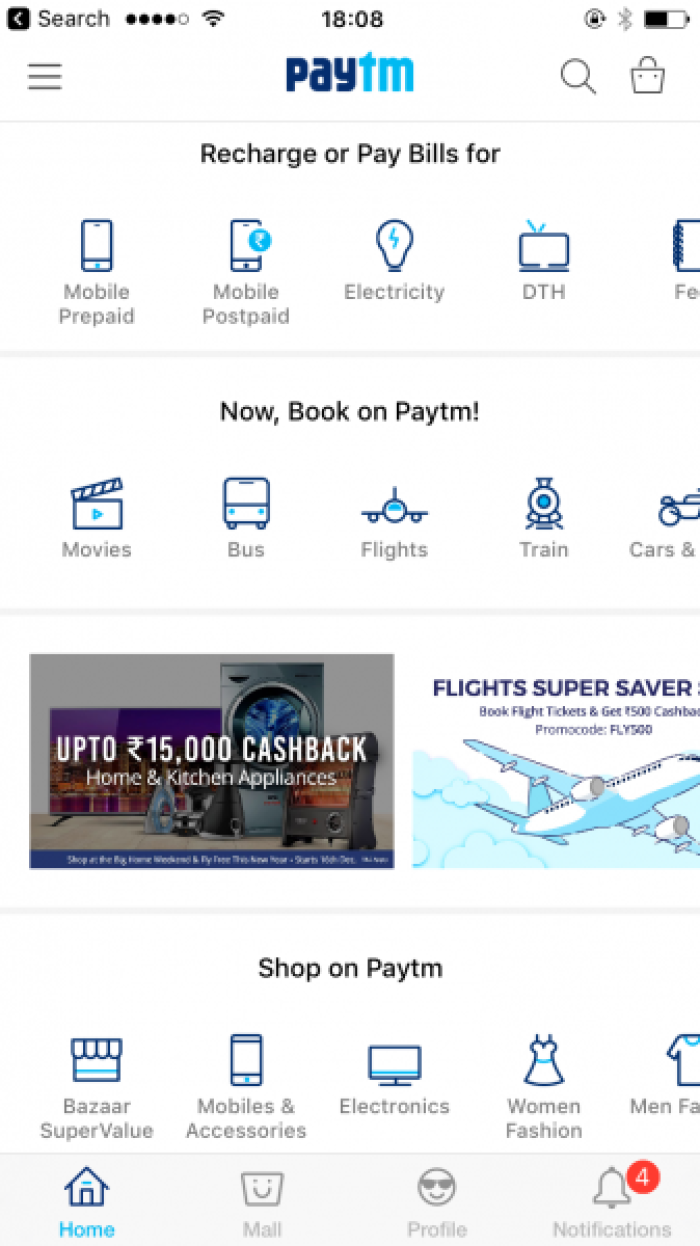

In India today, the options available for most citizens to pay cashlessly are limited to institutions that are increasingly looking to monetise citizen’s data – and it is not likely that the situation will be improving into the future. What options are available to Indians? Mobile wallets, usually accessed via a smartphone app, are one of the most common. The market leader is Paytm. This means you can pay at many – but by no means all – shops. Its mobile app offers a vast array of options that allow you to pay your electricity bill, book a flight, and buy products from socks to iPhones. Paytm is also looking to reach a broader audience: it recently introduced the option to pay at retailers through a phone call for people and places that lack a smartphone or Internet access. Thus, the amount of data that the mobile wallets are gathering about an increasingly broad user base is immense. Paytm is 40% owned, and reportedly has a very close working relationship with, the Chinese giant sales service Alibaba.

Demonetisation has resulted in a windfall for mobile wallets. Since demonetisation started, Paytm has been signing up half a million new customers daily. Sadly, the wallet companies are not always treating this sudden windfall with good grace, considering how millions of Indians are suffering from the shortage of cash. Take, for example, this billboard from the mobile wallet provider JioMoney:

Similarly, Paytm ran a campaign on Twitter, “Ab ATM nahi, Paytm karo”(No ATM, use Paytm). They also ran a TV advert with the tagline “Drama band karo, Paytm karo”, (Stop the drama, use Paytm), although this was revised. These approaches show a staggering lack of sensitivity when it comes to so much of India suffering under the burden of demonetisation.

But the problematic use of data is not limited to mobile wallets, it is also embedding itself within the banking sector. An alternative to mobile wallets, which may one day replace them, is the Unified Payments Interface (UPI). This enables the transfer of money between bank accounts via an app, if you know a unique identifier for that person such as a mobile or Aadhaar identification number. Yet the goal of UPI isn’t just to facilitate payments, it is also looking to take advantage of people’s data. At the moment, the costs of transferring money are borne by the consumer. But it is the hope of those behind UPI that this will change. Nandan Nilekani, former chair of the authority behind Aadhaar and an advisor to the National Payments Corporation of India that develops UPI, described the future in a report by Credit Suisse: “as data becomes the new currency, financial institutions will be willing to forego transaction fees to get rich digital information on their customers.” The goal of UPI is thus not merely to facilitate payments, but there is also the awareness of the value of people’s data, for example to sell services or to offer credit. As UPI develops further in the future, there is no wonder it was praised by Credit Suisse as helping “financial providers move from being data poor to data rich”. This has the potential to open-up new markets, but it is being done without little protection for the consumer and their data.

The available alternatives to cash for Indians, in the context of the limited protection available in India, all put their privacy at risk. Yet demonetisation has left many with no choice but to turn to the private entities looking to exploit their data. This is not a question of tax avoidance, criminality, or black money. Our financial transactions often stand as markers of the most intimate moments in our lives: the gift on our anniversaries, the medicine for a sick child. These intimate details are all there within our data. Taking away cash is taking away the choice that a person might make to keep these details private; taking away their agency, removing their autonomy and threatening their dignity. We may very well come to see the erosion of privacy as the legacy of demonetisation in India.