Can the police limit what they extract from your phone?

It is imperative that there is honesty as to the capabilities of extraction devices and clarity on what is taking place at a technical level.

In the last few months strong concerns have been raised in the UK about how police use of mobile phone extraction dissuades rape survivors from handing over their devices: according to a Cabinet Office report leaked to the Guardian, almost half of rape victims are dropping out of investigations even when a suspect has been identified. The length of time it takes to conduct extractions (with victims paying bills whilst the phone is with the police) and the volume of data obtained by the police are key areas.

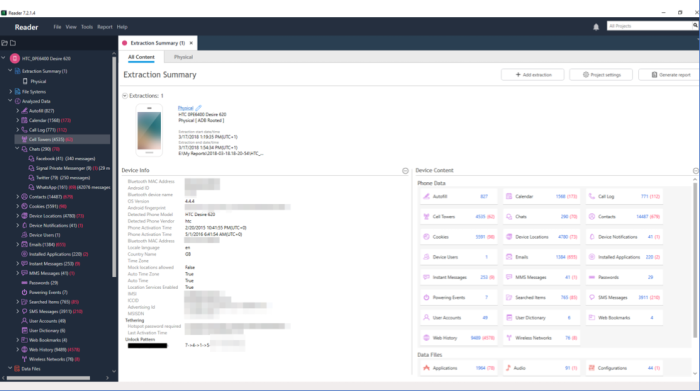

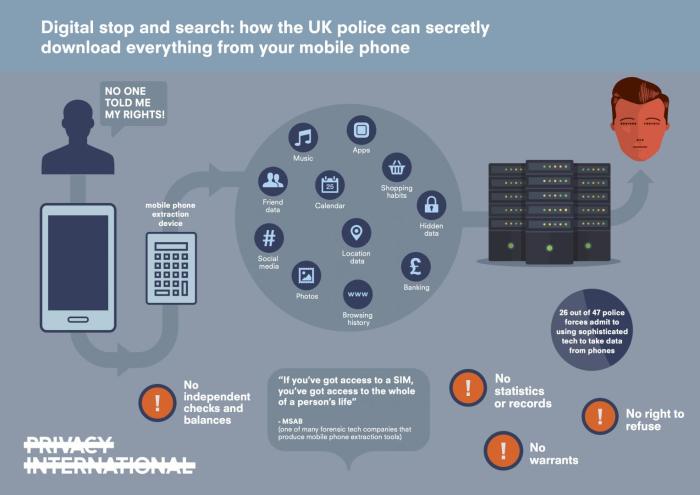

Mobile phone extraction involves the collection of vast quantities of data. Read the types of data that can be extracted here

To address fears that the police unreasonably grab everything - from your browsing history to all your messages and photos, potentially going back many years, one response is that they should limit what they extract. But is selective extraction possible, the idea that you can reduce what the police obtain from mobile phones?

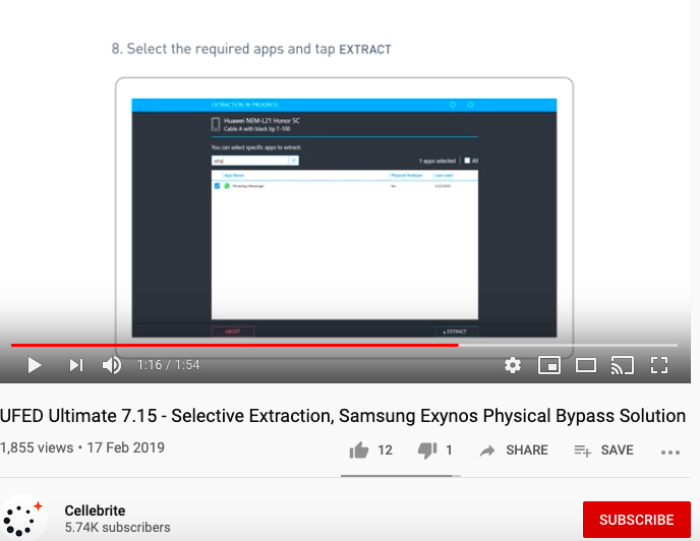

Israeli company Cellebrite, a lead manufacturer of data extraction devices states that the "Cellebrite Digital Intelligence Platform now supports Selective Extraction, meaning that police investigators need only collect data from a device that is strictly relevant to the case in question."

Our investigation into Police Scotland's Cellebrite 'cyber kiosks' reveals that the reality is perhaps more complicated. Despite stating they can limit what is 'viewed' by police, it is unclear whether the police still extract everything and then apply search parameters.

In addition, there are questions about whether it would be technically possible and forensically sound to limit a data type by date and time, given that you are then relying on the accuracy of a phone's time zone settings and how the data is stored. So is the reality, that the police could only limit via type e.g. messages and browsing history, but not by time or date?

It is imperative that there is honesty as to the capabilities of extraction devices and clarity on what is taking place at a technical level. This is not only so that victims rights are protected, but to ensure against the potential for abuse and misuse of personal data and to guarantee highly sensitive data is held securely. We've put some key questions that need to be asked in relation to selective extraction below.

What did we find out in Scotland

The Scottish Justice Sub-Committee on policing have conducted a lengthy inquiry into the proposed deployment of 'cyber kiosks' by Police Scotland. The process is different to how extraction is conducted in the rest of England and Wales - whilst cyber kiosks have the capability to store data, this has not been enabled. Instead the cyber kiosks are used as a 'triage' to identify devices that are of evidential value. If as a consequence of the kiosk triage items of evidential value are identified, then progression would be made for that device to be submitted to one of the Police Scotland Digital Forensic Hubs for detailed examination.

The kiosks are only used 'where the evidential relevance of the device is unknown' which may not in fact be the case in relation to a rape survivor who states what evidence is on their phone. Nevertheless, the comments made in relation to the ability to view data in a targeted and focused way may be informative of how selective extraction is purported to work. Unfortunately Police Scotland have refused to provide any information on Digital Forensic Hubs, where they do indeed extract data.

Police Scotland's data protection impact assessment states that cyber kiosks can 'view data on a device in a targeted and focused way i.e. only looking at what is necessary.' This is done via 'selected parameters' which 'refer to the areas of the device within which the kiosk has detected the existence of data available to view and to which filters are applied such as Text Messages, Cal Data, Chat (Whatsapp/Snapchat), Multimedia (Audio, Video, Photographs), Internet history, Email, etc - This also includes the ability to limit the search using a date range or keyword search criteria.'

> What is not clear, is whether using search parameters means that selective extraction is only applied at the viewing stage. But in order to obtain the data for the police officer to view, a broader extraction takes place. This is where clarity is essential.

It is further unclear, if the purpose is not simply 'view only' as is the case in Scotland using cyber kiosks, but to copy or extract the data, whether extraction can be limited in the way that may be possible if you are just wanting to view the data. Put simply, we don't know whether selective extraction is possible at the collection stage, what selective means in terms of the level of granularity and whether in fact selective extraction refers to search parameters at the later analysis stage.

Whether it is technically possible to limit at the extraction/collection stage relates to the fact that extracting data is complicated. It can depend on what phone you are using, the operating system and which types of extraction is used. The types of data that Police Scotland state in the data protection assessment that they can obtain, such as deleted data, indicates the use of certain methods of extraction (i.e. physical extraction) where it may not be possible to limit the types of data extracted, simply because of the way this extraction works.

In Cellebrite video on selective extraction using the UFED Ultimate 7.15 it instructs that a file system extraction is the method to use. Does this mean that selective extraction only works if you are able to carry out a file system extraction? The video explainer then instructs that you can 'Select the required apps to extract', but does not indicate any further limitation by date and time for example. So if the police inform a victim that they will only use selective extraction, this doesn't mean one or two messages, but all your WhatsApp messages, being communications with numerous individuals, including contact information, shared links, images and going back potentially years.

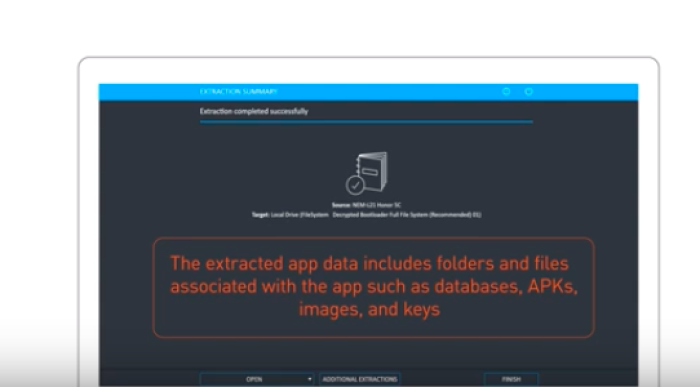

Even limiting by type still means a lot more data is collected than the owner of the phone may realise or understand. Cellebrite state in their video that "the extracted app data includes folders and files associated with the app such as databases, APKs, images and keys". The paucity of information means we just do not know the technical reality.

Police Scotland have stated that whilst search parameters can be used, they would not guarantee they would be used on every occasion because 'the data that would potentially be pertinent to an inquiry depends on what is under investigation.' They have also said that "it is possible that much of the data on a device may not be relevant to the investigation, but some of this may be assessed during triage and if irrelevant will be disregarded."

That it is possible to search without parameteres and to look and then 'disregard' again raises questions about how selective extraction works on a technical level.

All these questions not only support the need for clarity, but the complexity of the issue means that strict safeguards and independent audit must be in place. Unfortunately, to date, Privacy International have discovered that for many police forces, information that extractions have taken place, against whom, why and for what (i.e. not the data obtained itself but whether extractions have taken place) is not centrally recorded which makes audit impossible.

Detailed questions must be asked if we are to accept, on a technical level that the police really could and will limit what they extract, analyse and retain. As we have repeatedly said, mobile phone extraction is an area that needs effective scrutiny, clear legislation and public consultation. We are further concerned that a failure of the police to understand the tech or a failure to properly explain how it is working, could further undermine individuals' right to privacy.

Ideas for questions to ask

If you are looking at the use of selective extraction, whether you are a lawyer, organisation working with victims or individual seeking to make a Freedom of Information request, we think the follow questions should be considered:

1. Does the extraction device work by extracting all data and then limiting what a police officer can view via searches? i.e. the selective extraction is actually selective at the analysis stage rather than the collection stage.

2. Or can you limit the types of data that are extracted from the phone?

3. Or can you limit the type and date range of data that is extracted from a phone?

4. Is it technically possible to apply search parameters to search the phone without conducting extraction?

5. If you extract all data / all data of a certain type and then limit at the analysis stage, is all the data collected and retained, even if it is not searched or subject to analysis?

6. What processes and procedures do you have in place to ensure that selective extraction is in fact carried rather than broader search.

7. Is the system set up to ensure that it possible for independent audit to take place to review whether selective extraction has been misused, abused or officers have collected, analysed or retained more data than was expected / reasonable.

Is selective extraction enough?

Even should selective extraction be achieved, this is insufficient on its own to protect the rights of those subject to mobile phone extraction.

Mobile phone extraction technologies present great risks to privacy and we make the following recommendations in relation to use of this technology:

1. A search of a person’s phone can be more invasive than a search of their home, not only for the quantity and detail of information but also the historical nature. The state should not have unfettered access to the totality of someone’s life and the use of Mobile Phone Extraction requires the strictest of protections.

2. The police must have a warrant issued on the basis of reasonable suspicion by a judge before forensically examining any suspect’s smartphone, or otherwise accessing any content or communications data stored on the phone.

3. A clear legal basis must be in place to inspect, collect, store and analyse data from devices.

4. Reliance on consent is fundamentally problematic given the power imbalance inherent in the relationship between an individual and the police. Reliance on consent as the sole legal basis falls short of the requirements of the Law Enforcement Directive and there must be a basis in law.

5. There must be adequate safeguards to ensure intrusive powers are only used when necessary and proportionate. If law enforcement are to use vulnerabilities that constitute hacking, given the risk to device security, it needs to be considered whether this is ever proportionate.

6. The analysis of necessity and proportionality should include any effect the police action may have on the security and integrity of the mobile phone examined, or mobile devices more generally.

7. The owner and user(s) of any phone examined should be notified that the examination has taken place.

8. Anyone who has had their phone examined should have access to an effective remedy where any concerns regarding lawfulness can be raised.

9. There must be independent oversight of the compliance by the police of the lawful use of these powers.

10. Cyber security standards should be agreed specifying how data must be stored, when it must be deleted, and who can access.