Bulk surveillance is unlawful, says the High Court of South Africa

Updated on 7 October 2020

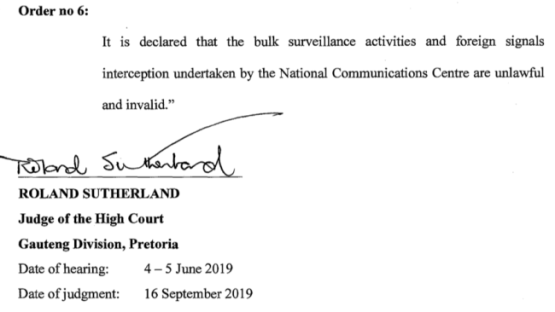

PI’s interventions contributed towards a historic decision made by the High Court of South Africa, which ruled that bulk interception by the South African National Communications Centre is unlawful and invalid. This decision held that secret and unchecked surveillance practices used by South African authorities must be explicitly stated in law so they can be considered and debated.

Today, the High Court of South Africa in Pretoria in a historic decision declared that bulk interception by the South African National Communications Centre is unlawful and invalid.

The judgment is a powerful rejection of years of secret and unchecked surveillance by South African authorities against millions of people - irrespective of whether they reside in South Africa.

The case was brought by two applicants, the amaBhungane Centre for Investigative Journalism and journalist Stephen Patrick Sole, after learning that state spies had been recording journalist Sam Sole’s phone communications for (at least) six months in 2008. The applicants challenged the constitutionality of certain sections of the regulatory framework of South Africa. Specifically, they argued that the Regulation of Interception of Communications Act of 2002 (RICA) and the National Strategic Intelligence Act 39 of 1994 (NSIA) violate the right to privacy and the Court should therefore declare them unconstitutional. Privacy International together with the Right2Know intervened to the case as friends of the court.

Six years ago, Edward Snowden revealed mass surveillance programmes in the US and the UK, among other states. Governments' refusal to avow these programmes began to crumble then. But, as we already highlighted in anticipation of this decision, it still takes significant amount of pressure to shed a light on these practices, including taking governments to court.

The rule of law prevailed today. The High Court concluded that such intrusive powers could not be read into other provisions or be construed as implied by the law. Such powers must be explicitly stated in law so they can be considered and debated. The Court was not persuaded by the South African intelligence authorities' plea that other states have similar practices. It stated

Our Law demands such clarity, especially when the claimed power is so demonstrably at odds with the Constitutional norm that guarantees privacy.

The High Court also refuted any claims that South African bulk interception concerned only communications coming from outside South Africa.

It is common cause that this form of monitoring would also capture communications between two South Africans, both of whom are in South Africa, if the signal passes through a server located outside South Africa.

It was not necessary for the Court to decide whether a law permitting bulk interception would be constitutionally compliant, as it concluded that there was no such law to begin with. However, the Court made it clear that it would not automatically accept the consitutionality of any such law, declaring that the need for clarity was especially acute "when the claimed power is so demonstrably at odds with the Consitutional norm that guarantees privacy."

Beyond the bulk interception practices, the High Court sided with the applicants on all six counts. The High Court concluded that "in several respects RICA is deficient in meeting the threshold required by section 36 of the Constitution to justify the subtraction of the rights" protected by the Constitution, including the right to privacy. It continued, "[l]ess restrictive means than those in force are feasible and ought to be enacted."

Specifically, the Court declared that RICA 1) did not provide a notification procedure for subjects of interception; 2) did not ensure sufficient judicial independence for authorising authorities; 3) failed to provide appropriate safeguards when an order was granted ex parte; 4) lacked appropriate procedures to be followed when state officials examine, copy, share, sort through, use, destroy and/store data obtained from interceptions; and finally, 5) failed to prescribe special procedures for cases when the subject of surveillance was either a practicing lawyer or a journalist.

In short, today the South African High Court found that secret, unregulated mass surveillance is unlawful.

In Europe, we are still waiting for the Grand Chamber of the European Court of Human Rights to pronounce on the legality of bulk interception in the United Kingdom and for the European Court of Justice to respond to three cases challenging bulk data retention and collection.