Switching Hats: Why South Africa’s Surveillance Industry Needs Scrutiny

In July 2015, representatives of a private company met in a parking lot in Pretoria, South Africa to sell phone tapping technology to an interested private buyer. What they did not know was that this buyer was a police officer. The police had been tipped off that the company was looking to offload the surveillance technology, an IMSI catcher, to anyone who would buy it. It is illegal to operate such surveillance technology as a private citizen in South Africa, and illegal to buy it without a government license.

There has been an uncomfortable increase in the powers of private security companies to conduct surveillance and sell surveillance technologies, particularly as the South African government has proved incapable to control them. Not that it does not try. “Investigat[ing] and counter[ing] espionage activities by the private security industry” is a top national intelligence priority of the State Security Agency (SSA), according to a 2014 document obtained by the Daily Maverick.

The South African government admits having difficulty controlling the proliferation of private security companies. Meanwhile, former intelligence public servants are running private companies that provide communications interception equipment. Some of these are actively seeking business from mining companies. How close is too close?

Switching Hats

Answering this question requires taking a look at South Africa’s surveillance industry, and its actual and prospective clients.

The former Head of Technical Intelligence Collection for the National Intelligence Agency, Manala Manzini runs Afrint Solutions. The company specialises in “electronic monitoring” and has exhibited at ISS World, the biggest international surveillance trade show. Manzini concurrently runs a “risk management” company that advises on security, in addition to his surveillance tech work.

Afrint shares an address with another surveillance tech firm, iSolv Technologies. They share a director, as well – Jayesh Nana, former Chairperson of the Technical Committee of the Office for Interception Centres (OIC), the centralised interception service for South African law enforcement. Nana has directed iSolv since 2004.

The OIC was an early client of iSolv Technologies. What division, if any, is there between this private company and the government’s communications interception agency? When campaign group Right2Know contacted the OIC about its capacities, they were referred instead to an iSolv employee.

Afrint and iSolv Technologies, two South African surveillance technology providers linked to former intelligence officials, share an office in this Johannesburg office park. Image: Google Maps.

There is no evidence that any of the companies discussed here engaged in illegal activity. Nevertheless, it is little wonder that South Africa’s SSA prioritizes monitoring the intelligence activities of private security companies.

Mining The Mining Market

August 2012, Marikana, South Africa: miners working for platinum mining group Lonmin launch an unauthorized workers’ strike to demand better pay. The ensuing month-long fight involved the miners’ union, the strikers, the South African Police and security forces. By the time negotiations ended, 44 persons had been killed, most of them workers. Some had been shot in the back. Four years later, it was revealed that the foremost representative of Lonmin during the Marikana strike was a covert agent of the SSA.

There have long been calls to shut the revolving door between the mining sector and government. Sensible environmental and labour safeguards cannot work unless senior decision makers are free of conflicting interests, activists argue. But this revolving door is less of a door and more of a merry-go-round when you throw private security companies into the mix.

It goes like this: a public intelligence official holds private assets in the mining industry, as a shareholder or director. Then he or she starts a security firm once leaving public service. He or she still holds interests in mining companies. Then, his or her security firm markets its private security and surveillance services as business intelligence to mining companies of the type in which he or she may still have assets. And mining companies make particularly attractive clients.

Foresight Advisory Group is a good example of this phenomenon. Foresight bills itself as a “fusion intelligence firm”; they offer to gather intelligence on internal and external rivals for companies. In 2015, Foresight CEO and former intelligence official Mthuthuzeli Jacob Madikiza went hunting for business at the African Mine Security Summit in Johannesburg, delivering a key note and sponsoring the event with a clear message that his company “has the tools and experience to minimise risk and make mining profitable.” In one pitch to the media, Njenje stated his case clearly: “If companies like Lonmin had advisers like Foresight perhaps they could have averted the tragedy that occurred on the day”.

Foresight was founded in 2014 by former Deputy Director General of South African Secret Service Gibson Njenje and a number of other intelligence and law enforcement bosses. Foresight is also an investment of investment firm Anglo African Capital – run by Njenje and top mining executive Heine Van Niekerk. Van Niekerk and his company Sable Mining were recently accused of improper payments to Liberian officials. As for Njenje, he started off in industry before resigning from a few companies, including mining outfits, to become an intelligence agent. He then boomeranged back to business after leaving the service in 2011.

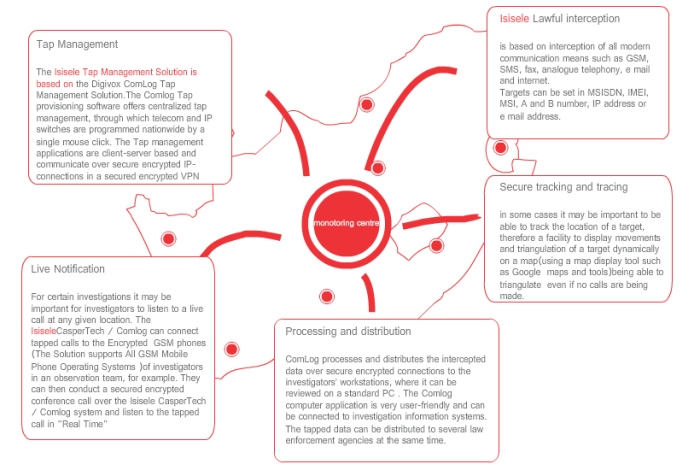

Isisele Technologies, a surveillance technology company, fits this same pattern. It sells a solution for the interception of communications directly off networks of service providers. Njenje again was also a director at this company and another, Freewheel Trade & Invest 16 (“Freewheel”). He is still an active director at a subsidiary of Isisele, the specialized logistics company Isisele Transtec Aviation.

Isisele sells network lawful interception technologies, such as this system. Image: Isisele.

A collection of mining interests orbits this small surveillance company. Freewheel, which also trades as Isisele, was first set up in 2008 by Dennis Jacobus Bishop, an early 100% shareholder of Sable Mining. (The same Sable Mining that was accused of bribery in Liberia). Other directors have included a former National Intelligence Agency agent (who also served at the Department of Environmental Affairs as a compliance specialist). A director of Isisele Technologies was coal and mining investor, Landlord Mojalefa Mbethe. All three companies, Freewheel, Isisele (the surveillance tech company) and Isisele Transtec (the logistics company) currently share the same active director.

Dizzy yet? Other companies are more explicit in the surveillance services they provide to the mining industry. One sponsor of the Mine Security Summit, Blue Thistle Consulting Solutions, offers “GSM listening equipment”, which could range from simple bugs to interception devices. Cobham, a large international defense technology company, also exhibited there, promoting its cell phone interception technologies and tracking equipment in the event brochure.

Mining companies are now being dangled powerful surveillance technology that, by law, is only supposed to be operated by public officials. Top (former) intelligence officials are heavily involved in mining interests, and concurrently involved in private companies that market surveillance technologies to the mining sector. The shadow of bloody strikes at Marikana makes for impressionable and eager buyers. This is, companies say, a “war” scenario in which police cannot be trusted but they can. “No longer can the police be expected to assist during times of labour unrest”, advertises D&K management services, a risk consultancy that also offers surveillance services. “Companies now need to take responsibility …into their own hands.” Are they taking communications surveillance into their own hands too?

Revolving Doors

A quick review of existing conflict of interest policies in this sector shows a striking, near-complete absence of any guideline on navigating this terrain to prevent conflicts of interest on sensitive matters related to people’s fundamental human rights.

Active office holders in the police service, military and intelligence services cannot concurrently be registered as security service providers according to the Private Security Industry Regulation Act 2001. The Public Service Act 1994, too, prohibits public office holders to take on extra paid work that could reasonably be expected to interfere with their official functions (section 30). This was the focus of the recent case in which a police officer, Paul Scheepers, was charged with illegally performing cell phone interception allegedly on behalf of a politician. (Scheepers’ security firm was also a distributor for a British company selling interception devices). There’s also an Executive Ethics Code. A recent report from the Public Protector Advocate found President Zuma to be in apparent breach of the code over a series of appointments allegedly influenced by the powerful Gupta family.

But absent is any more specific guidance on conflicts of interest in the law enforcement and intelligence sector. With help from the indefatigable South African History Archive, we filed requests under the Public Access to Information Act for the conflict of interest policies of five military, law enforcement and intelligence agencies – the Department of Defence, the South African Police Service, the Department of State Security – and two further departments in natural resource management and environmental affairs, the Department of Mineral Resources, and the Department of Environmental Affairs. We wanted to know if these agencies in any way regulated or monitored the employment, voluntary positions, company ownership or directorship of staff; former staff; consultants; and other paid representatives. We also asked the government’s security industry regulator, the Private Security Industry Regulatory Authority (PSIRA), for lists of all companies registered to operate in South Africa and the nature of their services.

We received no response to three requests, to the Department of State Security, the Department of Defence, and PSIRA. The Department of Mineral Resources reported holding no conflict of interest policies. A full response from the Police Services is still pending.

Only the Department of Environmental Affairs offered an insight into how it manages conflicts of interest. DEA staff who evaluate service provision bids are required to declare their interests, including stakes that they hold, family or friends with interests in the bidding company. They also must respect regulations around remunerative employment out of public service, which is generally prohibited if it would interfere with their ability to carry out their duties.

Recommendations

To the Private Security Industry Regulatory Authority:

- Publish register of private security companies that have registered with the Private Security Industry Regulation Authority in accordance with the Private Security Industry Regulation Act and its obligations as regulator of Private Security Industry.

- Undertake investigations into private security companies offering communications interception equipment for sale which, if used by private actors, would be in breach of both the Regulation of Interception of Communications and Provision of Communications Related Information Act, and the Electronic Communications Act, and publish results.

- Release results of any conflict of interest investigations involving private security firms, national security agencies, and/or mining companies.

- Release any internal guidance on conflict of interest policies currently operated, or previously used.

To the South African Police Service:

- Investigate potential sales of surveillance equipment to mining firms, which if used by private actors would be in breach of both the Regulation of Interception of Communications and Provision of Communications Related Information Act, and the Electronic Communications Act.

To the Department of State Security, and The Department of Defence:

- Reveal any internal guidance on conflict of interest policies currently or previously used.

Send comments, reactions and tips to [email protected]