Five ways your privacy is compromised without you realising

Photo credit: Pixabay

This piece was originally published in iNews

It seems that you can’t go anywhere online at the moment without being reassured that ‘we respect your privacy’ and being directed to a 2,000-word privacy policy. You probably just click ‘got it, thanks’ because who has the luxury to stop and think about what their ‘privacy’ actually means?

But privacy is something that starts becoming far less abstract when you can see how it is being threatened and undermined, every day and everywhere you go – even though there isn’t a privacy policy in sight.

Photo credit: Pexels

The city that’s so smart, it knows everything about you

If you live in a city, there’s a good chance it either already is working towards becoming, or aspires to be, a ‘smart city’. It’s a grand yet vague concept predicated on the idea that our transport, energy and municipal infrastructures can become more efficient self-regulating systems, based on analysing our mobile phone data and sensors embedded in everything from traffic lights to bins. Smart cities are something of a free-for-all, with anyone from municipal institutions to digital start-ups hoovering up data about us as we move around and interact with our public spaces. The Cityware project, for example, was able to track the physical interactions of 30,000 people using a combination of their Facebook profiles and smartphone’s Bluetooth signals.

Smart cities represent a market expected to reach almost $760 billion dollars by 2020. There are no clear checks and balances and with so many disparate actors involved, it’s easy to imagine that data breaches will occur. That may sound like a very abstract harm, but for a woman who visits an abortion clinic and doesn’t want anyone to know, her location data being compromised could have serious consequences.

Photo credit: Pexels

No such thing as free wifi

Next time you’re lured into a coffee joint with the promise of free wifi, you should be aware that what you are doing online could potentially be exposed especially, as is often the case, if the wifi network does not require a passcode to get online. Unsecure networks like this make it easier for cybercriminals to eavesdrop on what you do online. You should also be aware of ‘rogue’ wifi hotspots, which might deliberately use a name that’s similar to the coffee shop you’re currently sitting in but has nothing to do with them. So be careful before you connect to ‘Stirbucks_wifi’.

Photo credit: Wikimedia Commons

Police surveillance technology

It’s not just cybercriminals and shady corporations that should concern us. As well as the mass surveillance programs run by our intelligence agencies as shown by whistleblowers like Edward Snowden, the police also deploy a wide range of highly intrusive technology. Increasing use of facial recognition technology and body worn cameras mean that our ability to be anonymous is disappearing.

Photo credit: MaxPixel

Who is following you on social media?

If you’re not already concerned about the police’s reach into your life, how do you feel about them reading your social media posts? And using the aforementioned facial recognition technology on your photos? Guidance produced by the Association of Chief Police Officers on the policing of anti-fracking protests in 2011 stated: “Social media is a vital part of any […] intelligence picture.” And Whitehall chiefs monitored social media messages relating to public demonstrations against a massive cull of badgers in 2013.

Even if your social media accounts are all set to ‘public’, does that really mean your Facebook should be an open book to the police? Let’s use an analogy. If you were walking through a busy city centre, minding your own business and not doing anything suspicious, how would you feel if a police officer followed you wherever you went? Would this make you feel safer? And would you think that because you’re in public, you’ve forfeited your right to privacy?

In the same way, the trawling of our social media posts and photos just because we have an opinion about fracking or badgers should be cause for a lot of angry face emojis. As the UK Chief Surveillance Commissioner commented in 2015: “Just because this material is out in the open, does not render it fair game.”

Behind closed doors

OK, so let’s say you never go to a coffee shop again. And you’re going to close all your social media accounts. And never set foot in a public place again. Surely you can have some privacy within your own home, right?

Wrong. The preying sensors of modernity are as embedded in our homes as they are anywhere else. The internet of things’ (IoT) might sound like a cyber version of the ‘Day of the Triffids’, but internet-connected devices ranging from Smart TVs to smart meters, not to mention the HAL-9000-like virtual assistants like Siri and Alexa, are now remarkably prosaic.

At the same time as offering us convenience, efficiency, and automation, IoT devices are also building a detailed, revealing and intimate data profile about us, which manufacturers and government surveillance programmes can tap into.

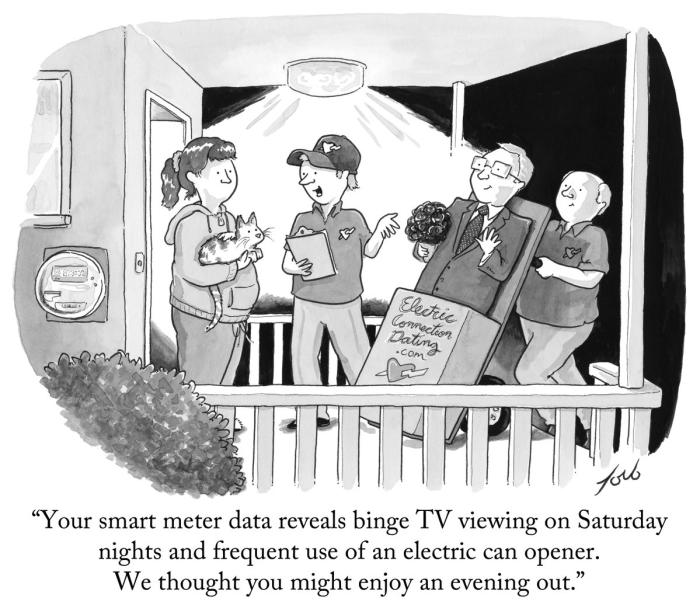

For example, smart meters collect energy usage data at high frequencies – typically every five, fifteen or 30 minutes. That level of granularity reveals how much electricity is being used in a home and when, which in turn can paint an intimate picture of a person’s household activities and lifestyle, and even indicate personal characteristics. One British analytics company Onzo boasted: “We take energy consumption data from smart meters and sensors. We analyse it and build a highly personalised profile for each and every utility customer”.

The internet of things is entwining our mundane experiences into a much bigger ecosystem that we can barely fathom the ultimate consequences of.

Photo credit: Anthony Quintano

So is the very notion of privacy in 2018 an oxymoron?

Corporations and governments would love for us to think so. It would suit them for us to willingly forfeit our data as the price of entry for living in a modern, digitised, networked society. But as Mark Zuckerberg found earlier this year, people aren’t happy about just being nodes in his vast digital network. We have a right to be left alone while we wander down the high street, stop off for a coffee, and even share a picture of it on Facebook before we return home and lock the door behind us.