“Truth exists but you have to find it”: Fighting disinformation on Facebook in Ukraine

“Truth exists, but you have to find it”, Oleksandra Matviychuk of Ukraine’s Center for Civil Liberties told me as I interviewed her in central Kyiv one week before the 2019 Ukrainian run-off election, “and in order to do so you have to make some effort”. We’re talking about her experience working on the ground in Ukraine, a country with a long history of battling against disinformation.

Activists in Ukraine have long experience navigating the noisy and chaotic environment that disinformation creates. I’ve come to Ukraine to talk to activists working in journalism, media monitoring, and civil liberties, and to ask about their experiences monitoring disinformation in the country – which is coming not only from Russia, but also from domestic politicians and others with money and power.

At PI, we’re focused on ensuring that the way data is used by political actors and advertisers does not facilitate the breakdown of democratic structures – and social platforms are an important player in this work. Disinformation and online political advertising play a role in shaping our beliefs about an issue or candidate, and social media platforms need to play a major role in ensuring that political messaging is transparent online, and disinformation is not algorithmically prioritised to shoot to the top of news feeds.

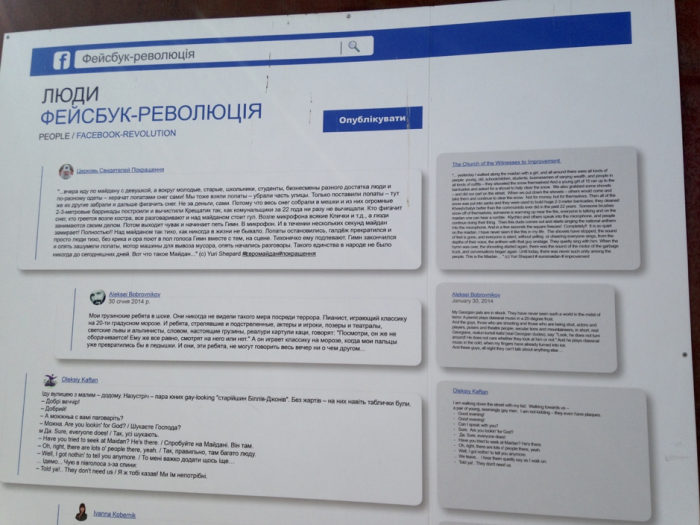

Social media platforms simultaneously play a crucial role in facilitating democratic structures by equalising voices and providing the potential to spread messages and ideas around the globe. Facebook and other platforms have been used around the world to grow and ignite social movements, including in Ukraine. Social media companies should recognise and accept their complex role in shaping our world and future.

“For us in Ukraine, Facebook is a very political place”

Facebook is Ukraine’s leading social media platform. After the Russian social platform VKontakte was banned in Ukraine in 2017, Facebook’s use in the country grew. “For us in Ukraine, Facebook is a very political place”, the executive director of an NGO that monitors disinformation and develops media literacy efforts in Ukraine, told me. Today Facebook is used by the leading political candidates and parties in the 2019 election to advertise and disseminate information to constituents. As the percentage of Ukraine’s population online (52.5% as of 2016) continues to increase, more people will inform their political views from online sources, including social media sites like Facebook.

Facebook and its other companies – Instagram and WhatsApp, as well as Google, Twitter, and others have been under increasing pressure to provide users strong protections against targeted political ads and disinformation.

Bending slowly to this pressure, Facebook has been implementing – in a handful of countries only – piecemeal transparency to political ads shown to users, as well as archiving political ads for a period of seven years.

“[The 2019 Presidential election] was the very first time that social media became important electoral instrument” Yevhen Fedchenko, co-founder of StopFake.org which focuses on highlighting Russian disinformation in Ukraine, told me.

In January 2019, Facebook announced that it would prohibit Ukrainian political ads bought outside Ukraine. The company also said it would create a library of political ads in Ukraine, which would be retained for seven years. These efforts, however came into force only two weeks prior to the polls opening, making it impossible to understand the totality of political ads bought.

Facebook and other social media corporations who have influence in political life in Ukraine and other countries have to understand their responsibility – which now they are trying to avoid. -Oleksandra Matviychuk

The organisations I spoke with generally expressed frustration with the transparency Facebook is offering Ukrainian users. Many of what were meant to be protections, are instead hinderances to civil society.

For example, organisations I spoke with that monitor disinformation and political advertising in Ukraine told me they repeatedly experience having their educational materials being banned or incorrectly marked as political content and taken down. Galyna Petrenko, Director of the NGO Detektor Media told me about her organisation’s experience with Facebook blocking educational content Detektor Media had developed from being promoted:

“We have our own weekly video programme for YouTube and Facebook about countering disinformation – we take some funny examples of disinformation from TV and show people what is wrong with this information. From our point of view, it’s a programme about media literacy, because we show the audience what is wrong with the content which they consume. But at the same time from the point of view of Facebook, it’s often political content and they just block it. They allow us to post it but they forbid us to promote it with advertising money. And we have constant conversations with technical support – it’s a weekly issue for us. We communicate with them and it’s difficult. [Facebook] ha[s] no local office in Ukraine, and we communicate with an office from abroad. As far as I understand, they do not have enough people in their team to understand Ukrainian language.”

This is something I heard repeatedly during my visit, when organisations try to reach out to Facebook for help getting their materials re-published after it was mistakenly blocked or because bots flooded Facebook with requests to delete the content, the company is extremely difficult to reach.

At present, there is no local office or team, and the position for a Warsaw-based public policy manager for Ukraine remains unfilled. Even when filled, I was told that what is needed is a team of local people, with deep regional understanding and experience, rather than one person left to manage all of this alone.

There have also been reports that the action Facebook has taken in the country to prevent people from outside of Ukraine from buying political ads is able to be circumvented relatively easily by political actors. For example, there has been reporting that buying and targeting political ads from outside Ukraine remains possible. One method reportedly being used to get around this block is to pay Ukrainians to rent out their Facebook account to sponsor ads.

There has also been reporting that Facebook’s tools do not appear to be functioning consistently. For example, Nina Jankowicz, a Global Fellow at The Wilson Center's Kennan Institute tweeted screenshots apparently showing ads disappearing from the ad library. Such inconsistency and lack of transparency goes against the purpose of the library itself. People, at a minimum, must be able to understand who is targeting political messages at them and why – a notion Mark Zuckerberg has written about and voiced support for.

Effective archiving of ads and messages is important to ensure fairness in the election cycle as well. Monitoring who is spending money to promote political messages is important, especially in the Ukrainian context, which Transparency International ranked 120th out of 182 in its 2018 Corruption Perceptions Index. Documenting who, what, where, and how content is targeted is important to holding those accountable for funding and promoting disinformation as well as their political claims.

“[Transparency is] not enough. The strategy has to be complex.”

The power of Facebook to delete, promote, and target content juxtaposed with the lack of power users have to contact the company, or to probe, or understand why content is deleted, promoted, or targeted is not unique to Ukraine, and has been central to many scandals Facebook has faced over recent years. As we at PI have said before, transparency is good yes, but the elephant in the room is that Facebook's business model is on shaky ground. And as Oleksandra Matviychuk told me, to completely address these problem, social media companies need to be willing to sacrifice a portion of their bottom line.

“I think that [transparency is] not enough. The strategy has to be complex. [Transparency] is built on desire of people to know more about this website but you know, people are not interested… If Facebook wanted to stop the spread of fakes, they will have to do things that will decline their assets.

Photo: Dotted around the country’s capital city Kyiv, are billboards from the two battling front-runners, the incumbent Petro Poroshenko and frontrunner, comedian/actor Volodymyr Zelensky. “Думай” – “think” say the Poroshenko billboards, with Zelensky’s billboards responding “Змінюй – “change it”.

What is clear is that how Facebook has so far handled the 2019 elections in Ukraine is not good enough. Even if the steps the company promoted were fully functioning, transparency is only the first step. A mechanical and generalist approach does not work in Ukraine and a team of people with regional experience is needed.

Government action in the form of regulation was desired by those I spoke with. At present there are two draft bills that were drafted under the guise of being aimed at addressing disinformation and fake news. While currently tabled, the bills represent a real threat to freedom of speech in Ukraine. According to Oleksandr Burmahin, a media lawyer at the Human Rights Platform whom I interviewed, the bills would allow websites to be pulled offline if the content was deemed harmful – and would put the onus on publishers to demonstrate it is not harmful, instead of requiring harm to be demonstrated prior to deletion. The bills have also come under criticism for allowing law enforcement access to data flowing through telecommunications providers, Burmahin told me.

Beyond these bills, there is a wide focus from civil society in Ukraine to increase media literacy in the country. The media literacy organisations with whom I spoke told me that there is a strong desire from people to become media literate and to understand how online manipulation happens. For example, the one organisation with which I spoke discussed how they had disseminated 101 guides on how to judge the accuracy of news, and received extremely positive feedback.

“There is a strong demand to become media literate right now. We were stunned when a few months ago we created some materials with pictures showing how to see if journalistic material is hidden political advertising or disinformation – how to see manipulations. And we got letters from heads of local communities that they needed this information so much that [they] printed it and put it in every school in the region - 73 schools and local canteens and restaurants – they made big posters. And we thought wow, the population is really fed up.”

And this is the silver lining – that while disinformation, dark advertising, and non-responsive monopolistic companies threaten democratic structures, people in Ukraine and around the world are getting fed up. People are getting tired of the arrogance of platforms like Facebook and the political actors that use such platforms and exploit data to attempt to manipulate our world views and realities. It was eye-opening to speak with people dedicated to figuring out how to combat these monsters, and to fight for access to the truth - Truth exists, but you have to find it, and in order to do so you have to make some effort.

PI is releasing a series of podcasts from our visit to Kyiv - you can find them here.

--

This piece was written by Sara Nelson who leads PI's project on political advertising and disinformation.