Our final report on Kenya's 2022 election in collaboration with The Carter Center Election Expert Mission

Prior to Kenya’s Presidential election in August 2022, PI travelled to Nairobi to collaborate with The Carter Center as part of their pre-election assessment team to assess the role of technology and data in elections. This is the final report resulting from that election expert mission.

- The Kenyan elections took place on 9 August 2022, with the results being announced on 15 August and confirmed by the Kenyan Supreme Court on 5 September

- PI joined The Carter Center in Kenya as part of a pre-election assessment team in July 2022 to identify and explore data protection issues around the elections

- The final report from the election provides an in-depth analysis of the implications of the Kenyan Data Protection Act for Kenyan elections, together with an explanation of the election technology used and a discussion of the data processing involved.

The final report on the 2022 Kenyan election is the result of a collaboration with the Carter Center as part of a joint pre-election assessment focussing on the use of technology in the run up to and during the Kenyan election which took place 9 August. The final report, published this month, follows our preliminary statement of September 2022.

Below we set out a few key observations in connection with the use of data and technology, as well as some of the key data protection incidents.

Key observations

Data protection legislation is a key element of the legal framework around election technologies

The adoption of the Data Protection Act in 2019 meant that for the first time the people of Kenya enjoyed specific protections around their personal data in an election cycle.

Privacy International engaged with and oversaw the development of the data protection legislation in Kenya. We continue to monitor its implementation, including through analysis of recent rulings and engaging key aspects of data protection and privacy in connection with the development of the Huduma Namba ID system.

The 2022 Kenyan election took place under an unprecedented Kenyan legal framework around data protection. The Data Protection Act came into force on November 2019, marking the adoption of a foundational protection mechanism for individuals to exercise their right to privacy.

The Data Protection Act imposed new legal obligations on political parties and public authorities involved in the election process, including the Independent Elections and Boundaries Commission (IEBC), to protect personal – including biometric – data processed during key moments of the election cycle, including during the campaign and in the voter register. The fact that all actors in the election cycle had data protection responsibilities and obligations was made clear by the Office of the Data Protection Commissioner in her Guidance Note for Electoral Purposes.

Legal obligations to protect personal data indeed emerged as important issues in several parts of the electoral context, including:

- Kenyans’ being registered as members of political parties without their knowledge or consent;

- An audit of the voter register uncovered “abnormal” transfers of voters to different polling stations; and

- Questions arising around the proclaimed sale of the voter register for a “fee”, as announced by the IEBC in July 2022.

Data protection agencies can play a key role in safeguarding the processing of personal data in the election context

The regulator established by the Data Protection Act is the Office of the Data Protection Commissioner (ODPC). The role of the Commissioner is to uphold and enforce the data protection legislation of the country, investigate complaints submitted by data subjects, and audit the processes of data controllers and processors to ensure compliance.

The 2022 elections provided an opportunity for the ODPC to monitor, regulate and take enforcement action on data processing activities by the different actors involved. In June 2021, the ODPC released a statement in response to a public controversy in connection to the involuntary registration of voters in political party membership lists. In November of that year, the ODPC clarified the scope of the data protection obligation in the context of elections through the publication of its Guidance Note for Electoral Purposes. Overall, the guidance note reiterates content already contained within the Kenyan Data Protection Act. Importantly, however, the guidance note explicitly covers data processing activities carried out by “all stakeholders in the electoral process.”

However, for data protection agencies’ work to be effective, transparency is key. While the ODPC seems to have undertaken action following reports of Kenyans’ being erroneously registered as members of political parties, information about meetings or negotiations relating to the alleged data violations was too often not relayed to local civil society organizations and voters, which aroused suspicion. Civil society organizations raised concerns that there seemed to be no investigation of what happened, no determination of who was responsible, and that there was no enforcement action taken nor penalties imposed.

Technology is fallible, and alternatives are important

The 2022 Kenyan election, like the 2019 election before it, relied on the use of Kenya Integrated Election Management System (KIEMS) kits. KIEMS is an electronic system comprising of tablets with biometric measuring features, and software used for voter registration, verification, and transmission of a digital copy of the results sheet from the polling station. The KIEMS software for the 2022 election was developed and provided by Smartmatic.

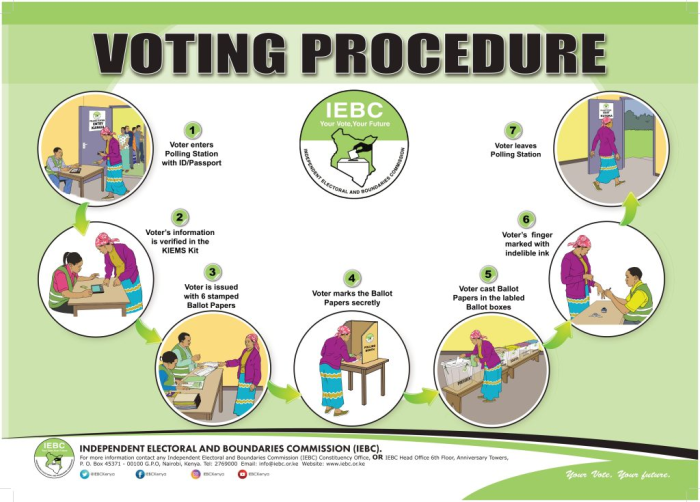

Image description: Step 1 Voter enters polling station with ID/Passport. Step 2 Voter's information is verified in the KIEMS kit. Step 3 Voter is issued with 6 stamped ballot papers. Step 4 Voter marks the ballot secretly. Step 5 Voter casts ballot papers into the labelled ballot boxes. Step 6 Voter's finger marked with indelibe ink. Step 7 Voter leaves polling station.

The KIEMS kit was used on election day for the following purposes:

- To identify and authenticate voters upon arrival at the polling station, by means of biometric voter identification through fingerprints. Prior to the election, the KIEMS kits had been used to register individuals onto the biometric voter register.

- To transmit vote tallies to the National Tallying Center for preliminary results calculations by scanning/photographing and sending digital copies of the results forms at polling station level (known as 34A forms) to the National Tallying Center and a public portal for the purpose of preliminary cross-checking of the transmitted tally.

The KIEMS kit’s role as main vector of voter identification was hotly debated, and the subject of litigation prior to the election. Initially, the IEBC had proposed to rely solely on the biometric voter register stored on the KIEMS devices for the identification of voters. However, after a successful legal challenge was brought by a number of organisations, including the Kenyan Human Rights Commission, the IEBC was ordered to distribute a manual register to each polling station to allow for voters to be manually verified, with the caveat that it should only be used in instances where the KIEMs kits completely failed and that there was no possibility of repair or replacement.

The inclusion of the manual register turned out to be essential. On election day, the IEBC reported that KIEMS kits failures necessitated resort to the manual register in 238 polling stations (of more than 46,000 in total) on election day. Of these, 84 were caused by a faulty removable memory card that stores the relevant parts of the voter register and other configuration and log files; the remaining 154 were due to logistical problems.

This was not the first time KIEMS kits had experienced failure - in the 2017 Presidential Election, 11,155 polling stations - 27% of the total 40,883 - were outside 3G or 4G range.

Reports by larger election observation missions, such as the EU Electoral Observation Mission and the National Democratic Institute, identified some problems with the KIEMS kits on election day, such as delays in identifying fingerprints, but found that most challenges could be addressed by backup measures built into the KIEMS system, such as via alphanumeric lookup and facial scanning with comparison against the national ID card.

It is clear that without the alternative of the manual registers, many individuals would have been prevented from voting.

Vulnerabilities to voters’ personal data can come from different places

Public-private partnerships

Smartmatic won the tender process run by the Kenyan government to provide the technology solutions mandated in the law; namely biometric voter registration, electronic voter identification, and electronic transmission of results.

It was later reported that the former elections technology provider in Kenya, OT Morpho (now known as IDEMIA), withheld Kenyan biometric voter data based on outstanding payments owed by the IEBC and refused to allow the transfer of that data to Smartmatic. In effect, IDEMIA laid claim to the voter roll and all the information contained therein. The issue was resolved outside of the courts, but it indicates a gray area in relation to the ownership of data produced by electronic information gathering systems.

Vulnerabilities capable of affecting the voter register

The IEBC commissioned KPMG to carry out an audit of the voter register. The audit report was presented in June 2022, only two months before the election took place. Among other reported issues, the audit raised questions about vulnerabilities in the biometric voter register that should be addressed over the coming electoral cycle (KPMG Audit, pp.25-26).

Gaps in the authorisation and provisioning of user access to the IEBC system

The audit noted a few irregularities in user access to the IEBC system, which is typically subject to authorisation by a supervisor and the ICT Director upon request. Among the issues flagged by the KPMG audit, some existing user accounts didn’t have access request forms; some others were created before the approval date set out on the form; some access request forms simply lacked approval.

Concerns on access controls around the databases hosting the register of voters

The KPMG audit noted inconsistencies between IEBC policy and the way databases relevant to the voter register were managed in practice. For instance, while the password policy required passwords to be renewed after 60 days, a database set the password to expire only after 180 days. Similarly, an IEBC policy requiring accounts inactive for 90 days to be deactivated wasn’t followed in practice.

The KPMG audit concluded:

Users with direct access to the database are privileged users and they pose the highest risk to the integrity of the Register of Voters. It is critical that access to the database is controlled and monitored in line with IEBC information security policies. To enhance the trust of the voter registration systems and the Register of Voters, we recommend tahat the Commission should conduct a comprehensive review of the access controls around the databases hosting the Register of Voters prior to next general elections.

Concerns on access controls around data held by IDEMIA

Upon reviewing the legacy voter registration system set up by IDEMIA, KPMG concluded that access controls around the databases hosting the register of voters were ineffective. Among other issues, the audit noted that individuals who were not registered as “Returning officers” or “Assistant returning officers” had made updates to voter data, there were users who were granted access to applications without user access forms or without appropriately completed/authorised forms, and there were excessive user access rights granted to users at the database level.

Data protection incidents, explained

Incidents in connection with data protection and technology emerged throughout the election. We explore key three issues that we identified as part of our pre-election assessment.

Registration of membership to political parties

The year prior to the election, over 200 complaints were made to the Office of the Data Protection Commissioner by individuals who learned their signatures had been registered as members of political parties without their knowledge or consent.

In June 2021, many Kenyans discovered they were registered as members of political parties without their knowledge and possibly without their consent. Voters were made aware of their registration with political parties as a result of a testing exercise ran by the Office of the Registrar of Political Parties on a national database recording political party members, the Integrated Political Party Management System (IPPMS). In June 2021, the Office of the Registrar of Political Parties upgraded the IPPMS, enabling voters to check their own details and membership of political parties. It was this test which led to the discovery of unwanted political party registrations.

The issue of individuals being registered to political parties without their consent isn’t new in Kenya; a previous portal to access party membership details in 2017 led to similar findings and outcry in the media. The difference in 2022 was the existence of the Data Protection Act, which enables more remedial action than was possible in 2017. Kenyans took to social media in response to this incident.

The Data Protection Commissioner tweeted that she had received over 200 complaints from aggrieved individuals and stated that she had met with the Office of the Registrar of Political Parties to ensure that the complainants were deregistered from the party membership lists they had erroneously been included in.

These complaints were acted on in consultation with the Office of the Registrar of Political Parties and led to safeguards, including additional consent mechanisms’ being built into the portal for endorsing candidates.

Abnormal vote transfers

In order to finalise the list of eligible voters, and in accordance with the Elections Act, the IEBC conducted three rounds of voter registration over October-November 2021, January-February 2022, and a final round ending on May 2022.

In parallel to the voter registration system, the Kenyan government introduced several options for registered voters to verify that they had been effectively registered and that their details were correct. During this verification exercise, many voters raised concerns that the electoral areas in which they had registered had been changed without their knowledge and approval. These issues were brought to the attention of KPMG as it was carrying out its audit.

KPMG confirmed in its audit report that it had identified a trend of “abnormal” voter transfers between the 2017 general election and May 2022.

Several of the mission’s interlocutors reported that voters had discovered that they had been transferred to a different polling station, often outside theirward, without their knowledge or consent. This phenomenon is inconsistent with the Elections Act of 2011, which states that only a registered voter can transfer their own registration to a different electoral area. The IEBC later announced that three IEBC officials had been arrested for involvement in illegal transfer of voters. On July 7, the chair of the IEBC announced that those officials were suspended and referred to the director of public prosecutions.

Sale of the voter register

The voter register is a key source of personal data, and often the spine which a range of actors build upon for subsequent data processing activities. As a result, the availability of personal data contained in the voter register, whether in whole or in part, is a key question to consider when undertaking a data protection analysis.

This investigation is all the more important in Kenya, where past research revealed that the voter register was openly available for sale with no protection or safeguards.

In July 2022, the Chairman of the IEBC announced in a keynote address during the National Election Conference that the voter register would be “available to stakeholders for a minimal fee.”

The legal basis for the distribution of the voter register, as well as the extent to which it would be modified – if at all – to limit the disclosure of sensitive personal data such as biometric data remains unclear. It also remains unclear whether the IEBC acted on this stated intention.

Under the Data Protection Act, any personal data in the register must be processed in line with data protection legislation. As highlighted by the Office of the Data Protection Commissioner, 39 processing personal data for inclusion on the register is done on the lawful basis that it is necessary to perform a public task. Uncertainty around this issue underscored the need for increased transparency and effective public communications around data protection issues.

Among other recommendations, Privacy International and the Carter Center recommend the following in connection to privacy and data protection safeguards for future elections in the Kenyan context:

To lawmakers

- It should be made clear in law and in relevant guidelines that personal data from the electoral register which has been made accessible is still subject to, and protected, by data protection law, including for onward processing.

To political parties

- Political parties and candidates should apply data protection safeguards to the personal information they collect and process. These safeguards should include the adoption and publication of data protection policies, undertaking data protection audits, proactively providing information about individuals whose data they hold about which data is held and how it is used, ensuring that they have a legal basis for each use of personal data, ensuring that third parties collaborated with for advertising purposes also comply with data protection requirements.

To the Office of the Data Protection Commissioner

- The ODPC should improve trust and transparency with the Kenyan people as the office is further established by effectively communicating decisions to the public and more openly challenge public and private actors, for example drilling down into the lawful basis for collecting this data.

- The Office of the Data Protection Commissioner could consider building on the guidance or codes of practice on data and elections, for example, by clarifying who should have access to the voter register and why. The guidance issued by the Office of the Data Protection Commissioner during the electoral cycle is a positive step. The issuance of guidance is an important process to help data controllers interpret data protection legislation.

You can find the full report below.

Background:

This project is part of PI’s work on Data and Elections.

In 2019 PI published “Technology, data and elections: A ‘checklist’ on the election cycle” in order to assist election observers update their working practices to ensure that personal data and digital technology are used to support, rather than undermine, participation in the democratic process and the conduct of free and fair elections.

See The Carter Center’s election observation factsheet for more information on how missions are conducted.