“When Spiders Share Webs”: Unveiling privacy threats of EU-funded INTERPOL policing programme in West Africa

Our exploration into the role of the EU-funded INTERPOL programme, the West African Police Information System, in externalising EU borders.

- WAPIS poses a threat to the fundamental human rights of numerous West African populations, including the right to privacy

- Documents disclosed to PI reveal that one of the rationales for the WAPIS programme includes curbing the free movement of persons in the ECOWAS area

- INTERPOL fails to uphold its responsibilities to protect human rights and mitigate risks of data protection abuses

- Transferring surveillance capabilities without firm safeguards in place is at best an act of egregious irresponsibility

Our briefing, “When Spiders Share Webs: The creeping expansion of INTERPOL’s interoperable policing and biometrics entrench externalised EU borders in West Africa”, explores the concerning human rights implications of the use of interoperable data-driven policing capabilities and biometric technologies in West African countries rolled out by the International Criminal Police Organisation (INTERPOL)’s European Union (EU)-funded West African Police Information System (WAPIS) programme. We make a series of calls on the European Commission and on INTERPOL to act around human rights and transparency concerns.

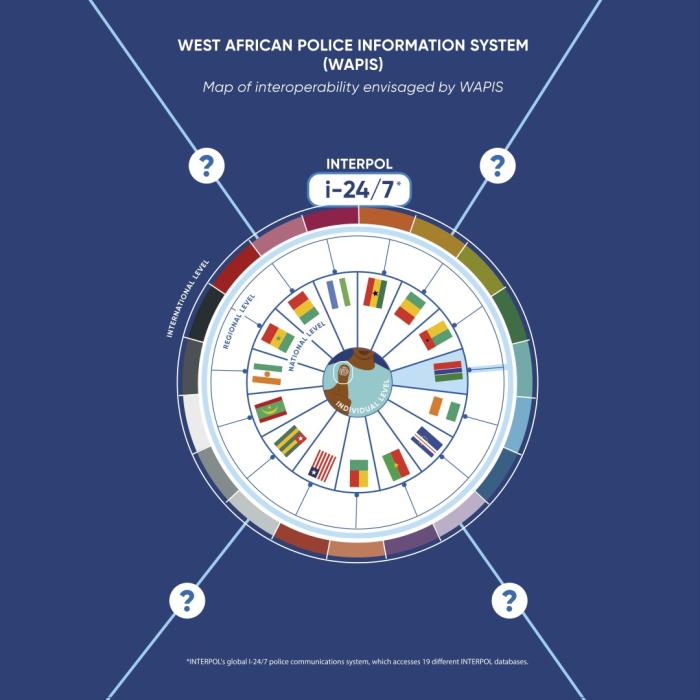

Funded by the EU and implemented by INTERPOL, the WAPIS programme sets out to digitise police information in West African countries via the establishment of national WAPIS data systems, whilst introducing the use of biometric technologies in the process. The objective is for each country to set up a database, which will in turn be connected to a regional data-sharing platform (not yet operational), as well as having the capability to link up at an international level to INTERPOL’s own global police communications system, named I-24/7, and to connect to external third parties (see image 1).

The WAPIS programme is rolled out in the free-movement area the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS), which includes Niger*, Togo, Sierra Leone, Ivory Coast, Burkina Faso*, Ghana, Senegal, Guinea, Benin, Cape Verde, The Gambia, Liberia, Mali*, Nigeria, Guinea-Bissau, with the addition of non-ECOWAS members Mauritania and Chad (*three countries withdrew from ECOWAS in January 2024 during the writing of this report). Our concerns include the apparent lack of repeated and adequate human rights due diligence during the course of the programme's deployment in West African nations, some of which do not have either effective legal frameworks, and/or functioning independent data protection authorities to govern and safeguard the data-driven policing introduced by the WAPIS programme.

Our report highlights the issue of “mission creep”, whereby the lines between counter terrorism and migration control are blurred, propelled by a logic that conflates irregular migration with criminality. Our research for this report draws from a series of documents released to PI under access to documents requests made to the European Union bodies, which reveal that one of the rationales for the WAPIS programme includes curbing the free movement of persons in the ECOWAS area, as the WAPIS data-sharing platform is seen as “the natural balancing measure to the Commission’s initiative to create a free movement and free establishment zone within the ECOWAS area”. According to this logic, increased data-driven policing is seen as a necessary counterbalance to free movement of people.

We found that without improved transparency surrounding WAPIS, combined with robust and regular human rights and data protection due diligence and safeguards that govern data-sharing and uphold data protection principles, the risks of human rights abuses as well as mission creep soar.

Transferring surveillance capabilities without firm safeguards in place is at best an act of egregious irresponsibility. In turn, WAPIS poses a threat to the fundamental human rights of numerous West African populations, namely the right to privacy, whilst also undermining the rights to freedoms of expression, association and assembly, the right to leave one’s country and the right to seek asylum, all of which are firmly enshrined in international human rights law.

PI acknowledges responses received from INTERPOL, the European Commission (EC) and the International Organisation for Migration (IOM) on the findings of this report which were shared with each organisation prior to publication. We incorporated into our report the information provided in these responses, which are also included in full as annexes. We also

followed up with INTERPOL with a letter which reiterated our enquiries and demands to them and welcomed engaging in constructive dialogue.

As a result of these concerns, we call on:

The European Commission:

- To disclose what human rights due diligence was conducted before and during the implementation of the WAPIS programme, including human rights impact assessment(s) and data protection impact assessment(s), and the content of this due diligence;

- Explain how the safeguarding of special category sensitive biometric data whose collection is facilitated by this project is ensured in WAPIS programme countries lacking in data protection legislation, and/or a dedicated national Data Protection Authority.

INTERPOL:

- Publish a named breakdown of databases external to INTERPOL that could receive data from, or share data with, national WAPIS systems via INTERPOL’s platforms should the government in question choose to allow such data exchange, including naming any national and EU databases, and actors external to both INTERPOL and the national authorities of a given programme country that may have access to WAPIS/AFIS databases;

- Disclose in full the human rights due diligence conducted in 2014, before the provision of technologies or capabilities (including trainings) to WAPIS programme countries, as well as any subsequent due diligence conducted as part of the programme, and prior to the contracting of private entities for the provision of such technologies or capabilities, and including data protection impact assessments and human rights impact assessments;

- Publish the memorandums of understanding between INTERPOL and authorities of WAPIS programme countries; the annual narrative and financial reports, revised work plans, and mid-term, as well as final evaluations; as well as the minutes of both WAPIS Programme Steering and Coordination Committee meetings and AFIS project Steering and coordination committee meetings;

- Provide information to detail at what stage of implementation the WAPIS programme is currently at in each programme country, and what plans if any exist for the implementation of the WAPIS Regional Platform since it is not yet in place;

- Provide information to detail what is the relationship between INTERPOL’s AFIS database and national WAPIS/AFIS systems, including what data sharing capabilities exist between the two;

- Provide information to detail how permission is secured and/or granted for a given member country to access data shared on an individual by another member country, via INTERPOL.

Our report comes in the wake of other findings of EU-border externalisation practises taking place at the expense of fundamental freedoms and human rights. Landmark research conducted by Lighthouse Reports and a consortium of international media outlets, including IRPI media and the Washington Post, entitled “Desert Dumps” and published in May 2024, exposes the role of the EU and individual European nations in funding and supporting North African government operations to detain tens of thousands of Black people and dump them in remote areas, including in deserts, in order to prevent them from migrating to the EU. Equally, in November 2023 the Border Violence Monitoring Network (BVMN) published their “Decoding Balkandac: Navigating the EU’s Biometric Blueprint” report in collaboration with PI, exposing the role of biometric data in violent pushbacks at borders between the EU and countries in the Western Balkans, again in order to prevent people from migrating into EU territory. Our new research thus contributes to a vast existing, and rapidly growing, body of evidence documenting use of technology and data in order to externalise EU borders and undermine the human rights of people on the move.

PI’s past work into EU-funded surveillance

This report is a continuation of our work challenging the Drivers of surveillance worldwide, which in the past has led us to make a series of joint complaints to the European Ombudsman on the transfer of surveillance technologies to third countries outside of the EU, under projects funded by the European Commission (EC) and other EU bodies. Our research revealed that seldom any human rights risk and impact assessments appeared to have been carried out prior to EU bodies’ engagement with third country governments in the delivery of said projects.

In November 2022, “The [European] Ombudsman [...] identified shortcomings in that the Commission was not able to demonstrate that the measures in place ensured a coherent and structured approach to assessing the human rights impacts of EUTFA projects”, confirming that adequate human rights due diligence had not been carried out on these projects which delivered surveillance capabilities. Later on, the Ombudsman’s inquiry into the EEAS made a series of suggested improvements for the EEAS to adopt in order for their human rights due diligence process to constitute as an acceptable alternative to a human rights impact assessment.