The EU's next budget is a huge threat to privacy - here's what must be done

Image source

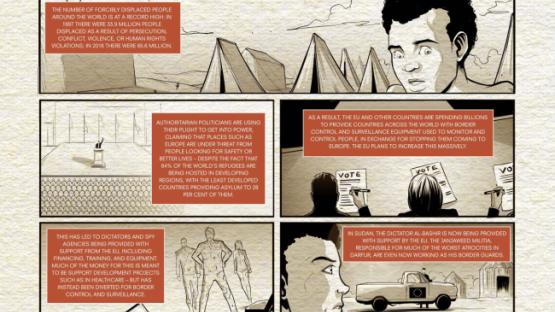

The EU extensively bolsters the surveillance and border control capabilities of governments around the world – and is set to dramatically increase such support. Below, we look at how some of these existing funds are being used, how their proposed expansion will undermine people’s privacy around the world for decades to come, and what needs to be done about it.

Migration has dominated the recent EU agenda and will once again be central during this week’s European Council meeting in Brussels, an important get-together for representatives of the EU member states’ governments charged with setting the broad political direction and strategy for the EU.

The meeting comes as leaders have come to power across Europe on anti-immigration and xenophobic platforms, and as the rest scramble to fend off what is seen as an existential threat posed by far-right populists by adopting their solutions.

This consensus has meant that the EU’s recent priorities and policies have been shaped by the drive to stop migration to Europe; a political strategy which has permeated throughout the EU’s current and future agenda, particularly its relations with non-member countries.

By prioritising migration control, the EU has been bolstering the development of surveillance and border control capabilities in countries around the world. Below, we look at how just one of these programmes, the Emergency Trust Fund for Africa, is already being used. It is now planning to dramatically increase such expenditure as part of the Union’s next long-term budget, currently being discussed.

What’s in the Budget?

Subject to agreement by the European Parliament and EU member states, the Multiannual Financial Framework (MFF) sets the EU’s budget for seven-year periods. Earlier this year, a draft was proposed by the European Commission which will manage expenditure of over a trillion euros between 2021-2027. The Commission hopes it will be signed off by the end of 2019.

Recent political summits in Bratislava and Rome have already made it clear that the EU’s most urgent priorities include reducing migration, supported by the fact that the largest proposed increases on expenditure from the previous budget is on migration and border control, which will see funding nearly triple to €34.9 billion.

In addition to building Europe’s own borders and surveillance capabilities, stopping migration has become the EU’s priority for its relations with non-member countries.

The new Neighbourhood, Development, and International Cooperation Instrument (NDICI), for example, will see money given to countries which ‘cooperate’ on migration control, and reward them with more funds based on their performance. It will replace a number of existing funds aimed at promoting democracy and human rights, development, and peace, and will have a budget of €89.2 billion – an 11% increase on the funds it replaces. By combining these with the objective of stopping migration, it will mean funds supposed to benefit people in developing countries can be used to pursue the EU’s own short-term interests.

The last Council meeting concluded that funds to be used for security (which is set to more than double to €4.8 billion under the next MFF) and the EU’s own borders should also be used for ‘external migration management’, while the €2.5 billion Internal Security Fund can also be used to ‘enhance cooperation with third countries in areas of interest to the Union’s internal security’.

Other funds foreseen in the MFF include the European Peace Facility, worth €10.5 billion and which can be used directly for financing military missions in line with the EU’s interests, the €13 billion European Defence Fund which will be used to develop new military technology, including things like lethal autonomous weapons. A new Union Reserve to be drawn from any unspent funds is also to be established, which aims to ‘tackle unforeseen events and to respond to emergencies in areas such as security and migration’.

Similarly to increases in expenditure for migration, the EU is also ramping up its security aid to foreign countries because of terrorism: funding by various bodies and funds from across the EU in counter-terrorism and ‘counter violent extremism’ more than doubled from €138 million in 2015 to €274 million in 2017.

Together, these increases in the EU budget will fund dramatic increases in the surveillance and border control capabilities of governments around the world.

The Problem

As border enforcement, criminal investigations, and intelligence gathering increasingly rely on gathering digital data, such a proposed expansion will – if unchallenged – undermine people’s privacy around the world for decades to come.

The main avenue which is supposed to protect against abuses of surveillance, the law, is widely inadequate across the EU across a broad range of powers and technologies, where it exists at all. Promoting the use of many of these same techniques and technologies such as the use of digital forensics and capacitating intelligence and police agencies in places which lack basic rule of law and with a history of targeting civil society makes abuses inevitable.

Worse than that however, spending money on curbing migration comes at the expense of other development aid work, betraying its purpose while simultaneously being counter-productive. While some of the money is described as aid, it is in fact being implemented by third parties, meaning the money will in fact go to private security companies based in Europe.

According to research by Oxfam 22% of the budget for the first two years of the over EU Emergency Trust Fund for Africa (of which 80% of its budget comes from development and humanitarian aid funds) was allocated to projects in the field of migration management. Another 13.5% goes to peace-building and security, with the largest part (between €121 million and €161 million, or 7% of the total budget) used to fund security forces in third countries, which are implemented by private and public companies.

Oxfam’s research into the fund also revealed that the instrument’s securitised approach resulted in insufficient safeguards, decisions taken without consultation, and insufficient attention to conflict-sensitive measures and ‘do no harm’ principles. It further resulted in 97% of the budget allocated to migration management funding migration containment, instead of projects “that enhance migration’s positive contribution to development and ensuring migration is safer and more orderly”.

What Can be Done?

Surveillance should not come at the expense of schools. It is imperative that no money which could be used for real development projects is used for the EU’s own security and migration interests. Expenditure should be re-prioritised towards long-term projects aimed at addressing root causes of some of the issues driving increased EU security expenditure, including terrorism and migration. These include projects aimed at conflict resolution, promotion of education, human rights, rule-of-law, anti-corruption, and good governance, as well as migration projects resulting in safe and humane conditions for people which save lives.

At the very least, any provision of capabilities must only be done if there are sufficient legal frameworks in line with EU and international human rights law for their deployment. There is now a body of jurisprudence of what is and isn’t legal under international human rights law, which can be used to guide any assistance. At the very least, any provision can be tied to the development of effective legal frameworks which protects against abuse, and which are in line with international necessary and proportionate principles.

Further, there should be democratic control over how the funds are spent. Without adequate safeguards, oversight, transparency, and accountability, these massively inflated funds risk being at best wasted, and at worst used for the promotion of human rights abuses internally and externally.

Safeguards could include basic vetting procedures to ensure that no funds are given to individuals, security units, or security authorities where there is evidence that they have been involved in human rights abuses or that assistance may contribute towards human rights abuses. To achieve this, any funds should undergo a privacy and human rights impact assessment prior to any award. Oversight could mean things like ensuring that projects are subject to Parliamentary oversight with sufficient a mandate and powers and to obtain relevant information and report publicly on their implementation. Transparency means ensuring that the funds should be made available on publicly, including copies of contracts and relevant procurement documents and all vetting, oversight, auditing, and impact assessments reports.

Ensuring that such basic measures are in place throughout the budget is essential. These public funds will have a massive impact on the lives of people around the world, and represent a dramatic shift in European security policy and its relationship with the rest of the world.

It is now vital that everyone has a say in this and makes their voices heard.

Emergency Trust Fund for Africa

Reacting to wide press coverage of the ’migrant crisis’, the EU launched the

Emergency Trust Fund for Africa in 2015 aiming to stop ‘irregular’ migration by, amongst other things, ‘enforcing the rule of law through capacity building in support of security and development as well as law enforcement, including border management and migration related aspects’ and contributing to ‘preventing and countering radicalisation and extremism. The fund, with a budget of 3.3 billion euros, contributes to 170 programmes across the Horn of Africa, North Africa, and the Sahel/Lake Chad.

Under the fund, the European Commission allocated €40 million in 2016 to countries in the Horn of Africa to strengthen the capacity of law enforcement officers by providing training, technical assistance and equipment. Specifically, the fund aims to assist in the establishment of specialised police units, increase capacity to conduct investigations, and enhance intelligence sharing between authorities. EU funding for border management in Sudan has reportedly included the funding of units involved in severe human rights abuses and in which personnel are former members of the Janjaweed militia, responsible for atrocities during the Darfur genocide.

€55 million was allocated earlier this year for enhancing border control measures in Tunisia and Morocco for the ‘purchase and maintenance of priority equipment, capacity building and development of necessary standards and procedures at national level’. The programme includes the provision of and training in ‘state of the art technology’, as well the establishment of screening system to allow border agencies to collecting data at border crossing points, outposts and coastal stations to be further analysed at the central level, and conduct risk analyses for travellers. In Morocco, the programme will develop an IT infrastructure collecting, archiving and identifying digital biometrics, increase aerial surveillance capabilities by providing equipment, and provide vehicles, surveillance, and communication equipment for different field units.

Last year, a €28 million programme funded by the Trust Fund began operations, aiming to develop a universal nationwide biometric ID system in Senegal by funding a central biometric identity database, the enrolment of citizens, and the interior ministry in charge of the system.

€15 million was allocated last year for a project in Algeria, Egypt, Libya and Tunisia building law enforcement agencies’ identification and investigation capacities. Activities include establishing a group of ‘cyber specialists’ ‘criminal analysts’, and ‘forensic specialists’ capable of conducting online investigations and collecting evidence from digital devices, training them, and providing them with ‘light equipment’.

Another EU-funded project in Tunisia ‘strengthening of the capacities of the Tunisian authorities in charge of border control and surveillance’ was finalised this year which established two operational rooms at the Tunisian National Guard as well as an integrated maritime surveillance system to centralise the data collected by the National Maritime Guard.

A project worth in excess of €8.5 million, Surveillance and Intervention in the Sahel (Burkina Faso, Mali, Mauritania, Niger, Senegal, and Chad), is underway aiming to increase the effectiveness of national security forces and their control of the borders, and enhance their intelligence sharing capabilities. In September the project reported that 158 personnel from Mauritania’s gendarmerie had been trained on ‘security, border management, [countering violent extremism], conflict prevention, protection of civilian populations and human rights’.

In 2016, €5 million from the trust Fund was awarded to Interpol for the development of a police database across Burkina Faso, Benin, Côte D’ivoire, Ghana, Mali, Mauritania, Niger, and Chad to enable them to ‘collect, centralize, manage and share police data’, and to train officers in the use of the system.

A €5 million project began this year aiming to ‘increase security levels and migration management capabilities in Cape Verde and Guinea Bissau’ by providing technical assistance, training programmes, institutional capacity building, legislation, and equipment. Specific objectives include training government agencies in issuing and checking identity documentation and increasing ‘the automatic collection of biographical and biometric elements of citizens’.