The use of social media monitoring by local authorities – who is a target?

In the UK, Local Authorities (Councils) are looking at people’s social media accounts, such as Facebook, as part of their intelligence gathering and investigation tactics in areas such as council tax payments, children’s services, benefits and monitoring protests and demonstrations.

This has particular consequences and a disproportionate negative impact on certain individuals and communities.

Social media platforms are a vast trove of information about individuals, including their personal preferences, political and religious views, physical and mental health and the identity of their friends and families.

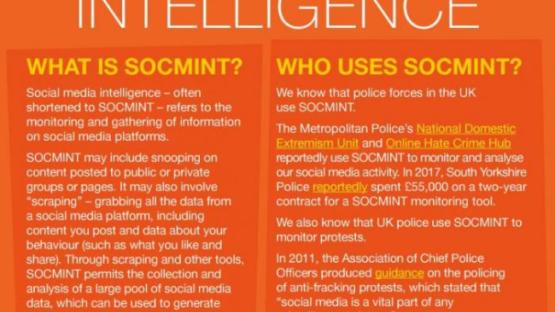

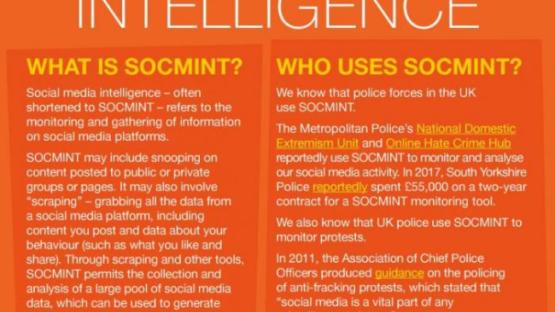

Social media monitoring, or social media intelligence (also defined as SOCMINT), refers to the techniques and technologies that allow the monitoring and gathering of information on social media platforms such as Facebook and Twitter which provides valuable intelligence to others, who want to monitor, profile, and manipulate people and groups.

Who uses such SOCMINT?

Governments across the world – democratic and undemocratic alike – have been developing a growing appetite for this “fast, cheap and easy” form of surveillance, and it has already been well documented that law enforcement agencies or security services are using SOCMINT to undertake overt and covert surveillance which is transforming intelligence and surveillance activities. But what about other governmental bodies?

Recent research by Privacy International has revealed that local authorities are also resorting to such techniques as part of various functions they are responsible for as mandated by legislation. These local authorities are looking at people’s social media accounts, such as Facebook, as part of their intelligence gathering and investigation tactics in areas like council tax payments, children’s services, benefits and monitoring protests and demonstrations.

For example, we found that Local Authorities in Great Britain are using ‘overt’ social media monitoring in the following areas:

- Recovery of unpaid Council Tax arrears

- Debt recovery

- Regulatory Services/Trading standards e.g. allegation of advertising illegal goods

- Neighbourhood Services

- Licensing

- Corporate Anti-Fraud teams / Revenues and benefits

- Environmental investigations

- Children’s social care

Who is being targeted?

Everyone is potentially targeted as at some point in our lives we all interact with local authorities as we go through some of the processes listed above.

The difference as to how will we be impacted?

For those social media users who does not control and amend their privacy setting in a certain way, their data is potentially fair game for social media monitoring. From our research, the respect given to an individual’s privacy by local authorities, in relation to what individuals say and do online, appears to be based on the arbitrary distinction of privacy settings.

In other words, if you have applied access controls, then you have a ‘reasonable expectation of privacy’ in relation to your social media posts. But if you do not apply privacy settings the data may be considered open source and overt social media monitoring can take place without any authorisation. This monitoring could be occurring without your knowledge or awareness, in a wide variety of their functions, predominantly intelligence gathering and investigations.

Life-changing decisions could be made on the basis of this intelligence but yet no quality check on the effectiveness of this form of surveillance on decision making. This has particular consequences and a disproportionate negative impact on certain individual and communities.

The disproportionate impact on people and communities

As in many other instances when it comes to the digitisation and use of new technologies, those in society in already marginalised and precarious positions and already subject to additional monitoring and surveillance are once again experiencing the brunt of such practices.

There are particular groups of the populations which are being impacted dramatically by the use of such techniques because they are dependent and subject to the functions of local authorities such as individuals receiving social assistance/welfare as well as migrants.

Newly established or reformed social protection programmes have gradually become founded and reliant on the collection and processing of vast amounts of personal data and increasingly the models for decision-making include data exploitation and components of automated decision-making and profiling. In some cases, our research has shown that local authorities in Great Britain will go so far as to use such information to make accusations of fraud and withhold urgently needed support from families who are living in extreme poverty.

We have seen similar developments in the migration sector where for immigration enforcement purposes governments are resorting to social media intelligence. Some of these activities are undertaken directly by government themselves but in some instances, governments are calling on companies to provide them with the tools and/or knowhow to undertake this sort of activities.

Project 17 is an organisation working to end destitution among migrant children in the UK. It works with families with no recourse to public funds (NRPF). They informed us that:

It is common for families with no recourse to public funds who attempt to access support from local authorities to have their social media monitored as part of a ‘Child in Need’ assessment.

This practice appears to be part of a proactive strategy on the part of local authorities to discredit vulnerable families in order to refuse support. In our experience, information on social media accounts is often wildly misinterpreted by local authorities who make serious and unfounded allegations against our clients.

In some cases, local authorities will go so far as to use such information to make accusations of fraud and withhold urgently needed support from families who are living in extreme poverty.

This practice often leaves families too afraid to pursue their request for support, which puts them at greater risk of destitution, exploitation, and abuse.

The various use cases outlined our report on the use of social media monitoring by local authorities should be seen as part of a broader apparatus being deployed, where social media monitoring plays a role. Privacy International’s work ‘When Big Brother Pays Your Benefits ’ examines the use of technology as a magic cure-all to socio-economic and political issues.

How to protect those most vulnerable

There is already vast evidence about the flaws and risks of using data from social media monitoring for decision including concerns about data integrity which may lead to potential misinterpretation and reliance upon misleading ‘evidence’, the lack of processes or procedures in place to undertake quality checks and audits, and the lack of transparency as to how social media profile could be used with much of this monitoring happening without a person’s knowledge or awareness.

As local authorities in Great Britain and elsewhere seize on the opportunity to use this treasure trove of information about individuals, use of social media by local authorities is set to rise and in the future we are likely to see more sophisticated tools used to analyse this data, automate decision-making, generate profiles and assumptions.

The collection and processing of personal data obtained from social media as part of local authority investigations and intelligence gathering, must be strictly necessary and proportionate to make a fair assessment of an individual. There needs to be effective oversight of use of social media monitoring both overt and covert to ensure that particular groups of people are not disproportionately affected, and where violations of guidance and policies do occur, they are effectively investigated and sanctioned.

It is urgent to ensure that the necessary and adequate safeguards are in place to protect those in the most vulnerable and precarious positions where such information could lead to tragic life altering decisions such as the denial of welfare support.

Therefore, we urge that local authorities should:

- Refrain from using social media monitoring, and should avoid it entirely where they do not have a clear, publicly accessible policy regulating this activity

- When exceptionally used:

- Local authorities should use social media monitoring only if and when in compliance with their legal obligations, including data protection and human rights.

- Every time a local authority employee views a social media platform, this is recorded in an internal log including, but not limited to, the following information:

- Date/time of viewing, including duration of viewing of a single page

- Reason/justification for viewing and/or relevance to internal investigation

- Information obtained from social platform

- Why it was considered that the viewing was necessary

- Pages saved and where saved to

- Local authorities should develop internal policies creating audit mechanisms, including:

- The availability of a designated staff member to address queries regarding the prospective use of social media monitoring, as well as her/his contact details;

- A designated officer to review the internal log at regular intervals, with the power to issue internal recommendations

Regulators who are mandated to oversee the activities of such bodies should call for guidance setting out guidelines, with concrete examples, by which local authorities may assess:

- What constitutes a legitimate aim for local authorities to rely on in order to conduct overt social media monitoring

- In what circumstances overt social media monitoring is just and proportionate to these legitimate aims

- Whether repeated or persistent viewing constitutes directed surveillance