When Local Authorities aren't your Friends

The UK Chief Surveillance Commissioners have repeatedly raised concerns about local authorities using the internet as a surveillance tool and suggested they conduct an internal audit of the use of social media sites. Privacy International sent Freedom of Information requests to local authorities in the UK to dig deeper into what's going on.

- A significant number of local authorities are now using 'overt' social media monitoring as part of their intelligence gathering and investigation activities. This substantially out-paces the use of 'covert' social media monitoring

- If you don't have good privacy settings, your data is fair game for overt social media monitoring.

- There is no quality check on the effectiveness of this form of surveillance on decision making.

- Your social media profile could be used by a Local Authority, without your knowledge or awareness, in a wide variety of their functions, predominantly intelligence gathering and investigations.

It is common for families with no recourse to public funds who attempt to access support from local authorities to have their social media monitored as part of a 'Child in Need' assessment.

This practice appears to be part of a proactive strategy on the part of local authorities to discredit vulnerable families in order to refuse support. In our experience, information on social media accounts is often wildly misinterpreted by local authorities who make serious and unfounded allegations against our clients.

In some cases, local authorities will go so far as to use such information to make accusations of fraud and withhold urgently needed support from families who are living in extreme poverty.

This practice often leaves families too afraid to pursue their request for support, which puts them at greater risk of destitution, exploitation, and abuse.

Eve Dickson, Project 17

Is your Local Authority looking at your Facebook likes? Just because it's in the open, doesn't make it fair game.

SUMMARY

In the UK, local authorities (local government) are looking at people’s social media accounts, such as Facebook, as part of their intelligence gathering and investigation tactics in areas such as council tax payments, children’s services, benefits and monitoring protests and demonstrations.

In some cases, local authorities will go so far as to use such information to make accusations of fraud and withhold urgently needed support from families who are living in extreme poverty.

Since 2011, the UK Chief Surveillance Commissioner, the regulator responsible for oversight of surveillance powers used by local authorities, has raised concerns about local authorities using the internet as a surveillance tool. By 2017, such was the concern that Lord Judge wrote to every local authority suggesting that they conduct an internal audit of the use of social media sites and the internet for investigative purposes .

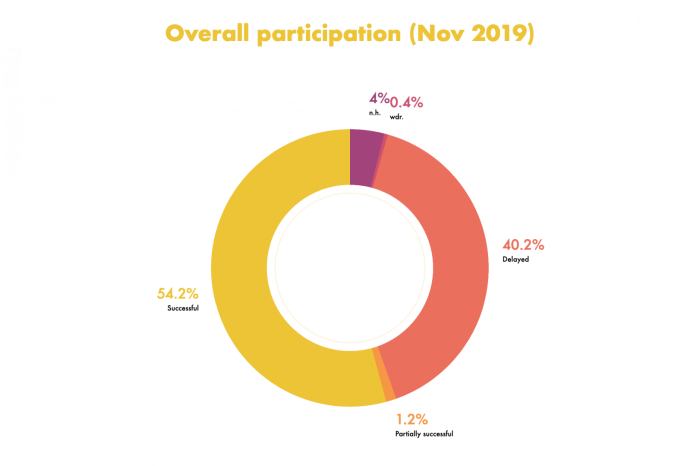

In October 2019 Privacy International sent a Freedom of Information Act request to every local authority in the Great Britain (251 recipients) in relation to their use of social media monitoring. We asked not only about whether they had conducted an audit in response to Lord Judge’s letter but sought to uncover the extent to which ‘overt’ social media monitoring in particular was being used and for what local authority functions.

The Surveillance Commissioner’s Guidance defines overt social media monitoring as looking at ‘open source’ data, being publicly available data and data where privacy settings are available but not applied. However, to be ‘overt’ it must also involve only a ‘one-off’ look at the individual’s social media. If this becomes ‘repeated viewing’, even of so-called open source sites, then this becomes ‘covert’ social media monitoring.

We have analysed 136 responses to our Freedom of Information requests, being those that had been received by November 2019. All responses are publicly available. In this report we include excerpts from the responses we received to better illustrate the use of these practices.

Our investigation has found that:

- A significant number of local authorities are now using 'overt' social media monitoring as part of their intelligence gathering and investigation activities. This substantially out-paces the use of 'covert' social media monitoring

- If you don't have good privacy settings, your data is fair game for overt social media monitoring.

- There is no quality check on the effectiveness of this form of surveillance on decision making.

- Your social media profile could be used by a Local Authority, without your knowledge or awareness, in a wide variety of their functions, predominantly intelligence gathering and investigations.

We analyse these findings below.

INTRODUCTION

Social media platforms are a vast trove of information about individuals, including their personal preferences, political and religious views, physical and mental health and the identity of their friends and families.

This wealth of information has attracted the interest of local authorities who are increasingly checking Facebook and other social media accounts. They are using this for investigations and intelligence gathering in areas such as children’s social care, council tax, fraud, licensing, benefits, neighbourhood services and debt recovery.

Perhaps more than ever, public authorities now make use of the wide availability of details about individuals, groups or locations that are provided on social networking sites and a myriad of other means of open communication between people using the Internet and their mobile communication devices.

Chief Surveillance Commissioner, The Rt Hon Sir Christopher Rose. Annual Report 2014-15

Social media monitoring

Social media monitoring refers to the techniques and technologies that allow the monitoring and gathering of information on social media platforms such as Facebook and Twitter.

The information can involve person-to-person, person-to-group, group-to-group and includes interactions that are private and public. For the purposes of ‘overt’ social media monitoring, this involves information such as messages and images that are posted publicly.

Whilst it is also possible to use certain tools to obtain data generated when you use a social media platform, such as location data or time of posting (i.e. meta data), it is not clear the extent to which local authorities can and do collect this data as part of ‘overt’ social media monitoring. Most local authorities currently search social media platforms manually.

As set out in Cheshire West and Chester Social Media Investigation and Review Policy, some of the sites that Local Authorities are likely to look at include Facebook, Twitter, YouTube, Snapchat, Instagram and Pinterest.

“Social Networking Sites (SNS) enable individuals, businesses and organisations to easily communicate with each other on a real time basis. Millions of users interact on these sites every day meaning that there is a vast amount of information recorded about users and their day to day lives.

Social media can be very diverse, but will often have some, or all of the following characteristics; The ability to show a list of other users with whom they share a connection; often termed “friends” or “followers”; The ability to view and browse their list of connections and those made by others within the system; Hosting capabilities allowing users to post audio, photographs and/or video content that is viewable by others; Social media can include community-based web sites, online discussion forums, chatrooms and other social spaces online as well.

For the purposes of this policy, examples of SNS include: Facebook, Twitter, YouTube, Tumblr, Flickr, Snapchat, Instagram, LinkedIn, Pinterest, Google+”

Data integrity

We are concerned that not enough consideration has been given to the inherent lack of data integrity, authenticity, veracity or the social context of conversations that may take place on social media. Leading to potential misinterpretation and reliance upon misleading ‘evidence’.

“Social media have been discursively framed as a kind of public sphere, and there are a range of limitations to this ideal, including issues of privatisation, categorical discrimination and unequal access. Yet public spaces are historically ephemeral, as any social actor’s engagement and disengagement with that space is relatively frictionless. Furthermore, the social actor can be present and visible in a public space while protected by the guise of relative anonymity. As an ideal, the outburst in the public square or the incendiary letter to the editor does not have an absolute bearing on the social standing of its author. Yet folding social media into open sources furthers the potentiality that the former are simultaneously a kind of public sphere and public record.”

Daniel Trottier, European Journal of Cultural Studies

Making judgments based on social media is plagued by problems of interpretation. What does it mean when you ‘like’ or share a post on Facebook? Are you endorsing it, raising awareness, or opposing it? What intelligence can be gained from who you interact with and the photos you post.

Obtaining evidence through the use of social media is often the most useful tool but requires particular care.

Swindon Borough Council

Reframing social media platforms, users and data in terms of intelligence gathering and criminality

We live in an age where our communications and interactions with individuals, friends, organisations, governments and political groups take place on social media. It has provided an opportunity for the instantaneous transfer and publication of our identities, views, interactions, and emotions. The growing intrusion by government authorities’ risks impacting what people say online , leading to self-censorship, with the potential deleterious effect on free speech, and other fundamental rights.

We have seen the way it is already being used to monitor recipients of welfare benefits, as part of immigration enforcement mechanisms as well as to crack down on civil society.

We may have nothing to hide, but if we know our local authority is looking at our Facebook, we are likely to self-censor. The impact is a reframing of social media platforms, users and data in terms of intelligence gathering and criminality.

…any new proposals for intelligence gathering in an internet age will raise issues over access to personal data and their use by the state, as well as broader concerns about the effect surveillance work might have on the economic and social value of the internet as a place of free exchange of ideas and information.

#Intelligence, DEMOS, Sir David Omand, Jamie Bartlett, Carl Miller

Whilst we may be living much of our lives onto social media sites, we provide information, however innocuous, that we are unlikely to share with local authorities when asked directly, unless we are given proper reason and opportunity to object.

“Democratic legitimacy demands that where new methods of intelligence gathering and use are to be introduced, they should be on a firm legal basis and rest on parliamentary and public understanding of what is involved, even if the operational details of the sources and methods used must sometimes remain secret.”

#Intelligence, DEMOS, Sir David Omand, Jamie Bartlett, Carl Miller

The future

As local authorities in the UK seize on the opportunity to use this treasure trove of information about individuals, use of social media by local authorities is set to rise and in the future we are likely to see more sophisticated tools used to analyse this data, automate decision-making, generate profiles and assumptions.

“Through our work representing destitute families seeking support and accommodation under section 17 of the Children Act 1989, Matthew Gold & Co regularly encounter local authorities monitoring families’ social media accounts as a means to try undermine the credibility of their claims of need.

MG&Co have seen local authorities use information to purport to justify a range of allegations against our clients which prove to be wholly unfounded. When families do not themselves have social media accounts, some local authorities have instead monitored accounts of third parties in their wider family or community context.

As local authorities are often secretive about their practices and sources of information, it can be extremely difficult for our clients to respond to the allegations, many of whom have limited education and speak English as a first language.

Unfortunately, this misuse of information can have extreme consequences for vulnerable children, who by law should be protected. MG&Co has represented multiple families for whom support was been refused or delayed based on misinterpretations of information on their parents or third parties’ social media accounts. This has caused hunger, distress, homelessness and the threat of even street homelessness. Yet, upon us challenging the decisions, in every case the local authority provided support because it was accepted that the children were in need”.

Rachel Etheridge, Matthew Gold Solicitors

ANALYSIS OF FINDINGS

1. A significant number of local authorities are now using 'overt' social media monitoring and this substantially out-paces the use of 'covert' social media monitoring

Overt social media monitoring involves the “Casual (one-off) examination of public posts on social networks as part of investigations undertaken is allowable with no additional RIPA consideration.” Whereas “Repetitive examination/monitoring of public posts as part of an investigation” constitutes ‘covert’ monitoring and “must be subject to assessment and may be classed as Directed Surveillance as defined by RIPA.”

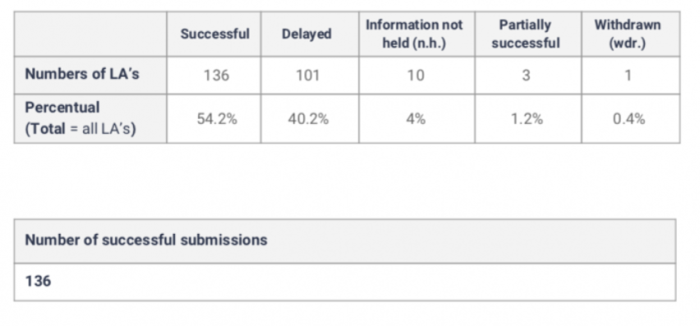

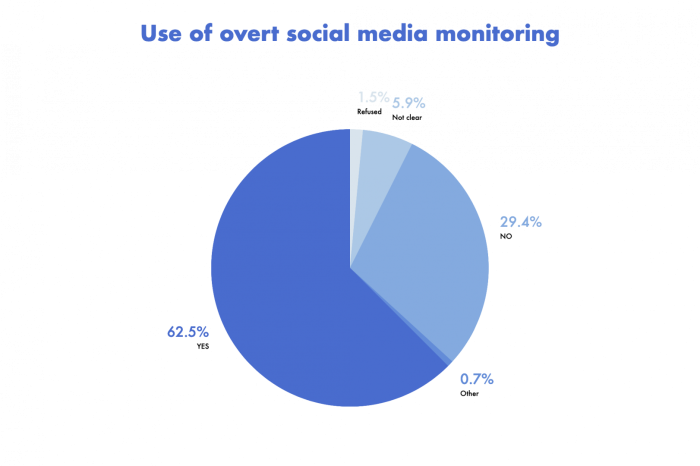

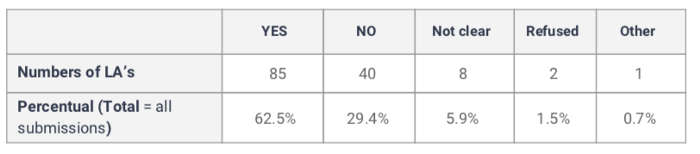

- We reviewed responses to our FOIA request from 136 local authorities

- 62.5% of local authorities are using 'overt' social media monitoring

- 31% of local authorities are using 'covert' social media monitoring

- 23.1% of local authorities who aren't using 'overt' social media monitoring still have a policy/guidance on carrying out this type of surveillance

“The use of the internet as an investigative method is now becoming routine.”

London Borough of Ealing RIPA Policy and Guidance

We believe this indicates that 'overt' social media monitoring is a significant tactic used by local authorities. Particularly given that even local authorities who do not use social media monitoring, address it in their policies and guidance. This may signify that this tactic is set to soar in popularity.

Question: Are you able to state how regularly social media is used?

Answer: We estimate to be approximately once or twice a week on average but can vary. Only Facebook is used.

Allerdale Borough Council

As noted in Colchester’s ‘Use of Social Media in Investigations Policy and Procedure 2018/19’

Social Media has become a significant part of many people’s lives. By its very nature, Social Media accumulates a sizable amount of information about a person’s life, from daily routines to specific events. Their accessibility on mobile devices can also mean that a person’s precise location at a given time may also be recorded whenever they interact with a form of Social Media on their devices. All of this means that incredibly detailed information can be obtained about a person and their activities.

Social Media can therefore be a very useful tool when investigating alleged offences with a view to bringing a prosecution in the courts. The use of information gathered from the various different forms of Social Media available can go some way to proving or disproving such things as whether a statement made by a defendant, or an allegation made by a complainant, is truthful or not. However, there is a danger that the use of Social Media can be abused, which would have an adverse effect, damaging potential prosecutions and leave the Council open to complaints or criminal charges itself.

2. If you don't have good privacy settings, your data is fair game for overt social media monitoring.

We are concerned that the respect given to an individual’s privacy by local authorities in the UK, in relation to what individuals’ say and do online, appears to be based on the arbitrary distinction of privacy settings.

This distinction is supported by the Home Office guidance and guidance from the Regulator (the Investigatory Powers Commissioner) whose annual reports document concerns related to local authority use of social media monitoring.

The policies of local authorities reflect the belief that "the author has a reasonable expectation of privacy if access controls are applied." But "where privacy settings are available but not applied the data may be considered open source and an authorisation [to access it] is not usually required."

Where privacy settings are available but not applied the data may be considered open source and an authorisation is not usually required. The fact that an individual is not told about “surveillance” does not make it covert. Notice the words in the definition of covert; “unaware that it is or maybe taking place.” If an Officer decides to browse a suspect’s public blog, website or “open” Facebook page, this will not be regarded as covert.”

Blaenau Gwent Country Borough Council Guidance

We are concerned that the arbitrary distinction of privacy settings to decide whether or not something is ‘open source’ in relation to social media is flawed and unsophisticated.

As noted by authors Lilian Edwards and Lachlan Urquhart, privacy settings constantly change and can apply differently to different content. In addition, social media sites are motivated by making user content as public as possible and thus difficult for an individual to protect. individuals may share without necessarily being aware who can access their information and how it is used. We further note they may differ depending on other factors such as jurisdiction and device used.

… contrary to popular belief, control of what data about you is public on social media is not simply a matter of easy voluntary choice. Accordingly, the common retort – if you didn’t want people to read it, why did you make it public? – is not in fact a sensible question to ask. We would argue this contributes strongly to an argument that material placed on “open” social media can still carry with it reasonable expectations of privacy.

…privacy settings vary from platform to platform and also change constantly over time in a way that requires constant vigilance of users to maintain a privacy status quo. Different privacy settings, and different changes, apply to different types of content e.g. posts, comments, groups, photos, friends list etc. On most sites, as with Facebook, the overwhelming motivation is to make as much material as possible public to maximise growth of audience and collection of data for marketing revenue. Hence it is well known that many are deluded in their belief that they have adequately protected their privacy via code controls. Indeed Madejski, Johnson and Bellovin found that in a small study of 65 university students, every one had incorrectly managed some of their Facebook privacy settings, thus displaying some personal data to unwanted eyes.

Lilian Edwards and Lachlan Urquhart, ‘Privacy in Public Spaces: What Expectations of Privacy do we have in Social Media Intelligence

To elaborate, if you don’t know how to check your privacy settings or use social media platforms that have no settings, your information will be treated as ‘open source’ and local authorities can look at it, (as they state in response to our Freedom of Information Requests) for ‘intelligence gathering’ and ‘investigations’, without you ever knowing.

By contrast, where individuals have strict privacy settings and use platforms that offer controls, these individuals are granted ‘a reasonable expectation of privacy’ in relation to their social media posts and not subject to the same intrusion.

For example Barnsley MBC’s Local Code of Practice states that use of open source material prior to an investigation ‘should not normally engage privacy considerations’ and individuals should expect to have a ‘reduced expectation of privacy’ if they post publicly.

“Investigating officers who use social media and the internet generally as a source of information on suspects or potential suspects must be particularly careful to understand how far they may go before a RIPA authorisation is required. Whilst the use of open source material prior to an investigation should not normally engage privacy considerations, if the study of an individual’s online presence becomes persistent, or where material obtained from any check is to be extracted and recorded, RIPA authorisations may need to be considered.”

“There may be a reduced expectation of privacy where information relating to a person or group of people is made openly available within the public domain, however in some circumstances privacy implications still apply. This is because the intention when making such information available was not for it to be used for a covert purpose such as investigative activity. This is regardless of whether a user of a website or social media platform has sought to protect such information by restricting its access by activating privacy settings.”

“Where information about an individual is placed on a publicly accessible database … unlikely to have any reasonable expectation of privacy over the monitoring by public authorities of that information. Individuals who post information on social media networks and other websites whose purpose is to communicate messages to a wide audience are also less likely to hold a reasonable expectation of privacy in relation to that information.”

(emphasis added)

Other local authorities make it very clear that it is up to the individual to check their privacy settings and to post publicly is done ‘at their own risk’. Cheshire West and Cheshire state that:

“Some users will not set any privacy settings at all meaning that the information they post is publicly available. Individuals that operate with no, or limited, privacy settings do so at their own risk…

Other users will set their privacy settings to the highest control. These people do not want their content to be in the public domain. Respect should be shown to this content under Article 8 of the HRA, as well as the Data Protection Act 2018.

….Whilst data may be considered ‘open sources’ where privacy settings have not been engaged and legal authorisation to view the information may not be required, the repeat viewing of ‘open source’ information may be considered directed surveillance and would be considered unlawful unless RIPA authorisation has been sought.”

This puts the onus on individuals to understand and check their privacy settings, and fails to recognise that:

- Privacy settings vary from platform to platform and also change constantly over time in a way that requires constant vigilance of users to maintain a privacy status quo.

- People share vastly more personal information about themselves, their friends and their networks than they would if a local authority requested this type of information.

- Control of what data about you is made public on social media is not simply a matter of easy voluntary choice. For example, in 2018 a Facebook bug changed 14 million people's privacy settings .

This approach to social media settings further fails to adapt to what society believes should be counted as public or private, or indeed to our own ideas and presumptions about what we post on social media and who should have access to it and for what purposes.

Social attitudes towards what is private or public, and therefore what counts as intrusive or not, are blurred and changing. It is unclear whether social media platforms are public spaces, private spaces, or something else altogether.

#Intelligence, Demos

Repeated viewing

When social media monitoring of 'open source' data involves repeated viewing of an individual’s social media, authorisation is required. The Investigatory Powers Commissioner has advised that repeat viewing of a suspect’s profile on “open sources” sites may constitute directed surveillance and require a higher level of authorisation (known as RIPA* authorisation).

Casual (one-off) examination of public posts on social networks as part of investigations undertaken is allowable with no additional RIPA consideration. Repetitive examination/monitoring of public posts as part of an investigation must be subject to assessment and may be classed as Directed Surveillance as defined by RIPA.

Arun District Council Guidance on the Use of Social Media in Investigations

Yet there is a lack of consistency as to what constitutes repeat viewing. From the Freedom of Information responses, we have received and the policies some local authorities have disclosed with these responses, it appears that if a local authority spent time looking at an individual’s social media, kept that page open, took screenshots of the page and stored those, this may be ‘overt’ and does not require authorisation or result in any checks and balances.

Cheshire West and Chester:

“The following relates to the accessing of publicly available SNS data only:

… Once content available from an individual’s Social Media profile has been identified as being relevant to the investigation being undertaken, it needs to be recorded and captured for the purposes of producing as evidence. Depending on the nature of the evidence, there are a number of ways this may be done. Where evidence takes the form of a readable or otherwise observable content, such as text, status updates or photographs, it is acceptable for this to be copied directly from the site, or captured via a screenshot, onto a hard drive or some other form of secure storage device, and subsequently printed to a hard copy. Where evidence takes the form of audio or video content, then efforts should be made to download that content onto a hard drive or some other form of storage device such as a CD or DVD. When capturing evidence from an individual’s public Social Media profile, steps should be taken to ensure that all relevant aspects of that evidence are recorded effectively. For example taking a screenshot of a person’s Social Media profile, the Council officer doing so shall make sure that the time and date are visible on the screenshot in order to prove when the evidence was captured.”

Blackburn with Darwen Borough Council’s procedural guide, for example, states that spending over three weeks googling or otherwise monitoring a person’s name on various dates during that time may not fall within the Regulation of Investigatory Powers Act [RIPA ], although it would require use of their non-RIPA form. Other local authorities refer to ‘one-off searches’ of social media.

17. Non –RIPA forms are likely to be required if the proposed activity does not fall within RIPA but can be considered to be likely to breach a person’s right to respect for his private and family life. So if you are going to spend over three weeks googling or otherwise monitoring a person’s name on various dates during that time then that should trigger a NON RIPA form at the very least. It may depend upon how many hits you may click on during those weeks and the type of information uncovered. Consider whether what you are seeing really is intended to be ‘open source’ even if you do find it on an open source site.

Blackburn with Darwen Borough Council, Procedural Guide for the use of covert surveillance and covert human intelligence sources

Lincoln City Council states that two visits are acceptable before it amounts to Directed Surveillance.

“It is considered proportionate to visit a Social Media sites where there are no privacy settings twice in connection with an investigation (for example benefit fraud) but any further visits could amount to Directed Surveillance and require RIPA authorisation.”

Lincoln City Council

3. There is no quality check on the effectiveness of this form of surveillance on decision making

We asked local authorities if they were able to state how regularly social media monitoring is used and if so to provide figures. We examined the responses of those local authorities who stated that they do use overt social media monitoring.

- We reviewed responses to our FOIA request from 136 Local Authorities

- The majority of the local authorities who conduct ‘overt’ social media monitoring, do not monitor i.e. audit this use of 'overt' social media monitoring.

- In most cases classed as ‘overt’ social media monitoring, there is rarely any form of authorisation and there is an absence of audit and accountability.

- There is no guidance or requirement from the Investigatory Powers Commissioner for local authorities to track and audit the use of overt social media monitoring.

- 60% of local authorities who use 'overt' social media monitoring do not provide training for staff

The responses to the question which sought to find out whether local authorities were reviewing the use of overt social media monitoring were confusing, which makes it difficult to draw out any statistics from the replies. There was no clear procedure in the guidance or policy documents disclosed.

The large majority of local authorities who use overt social media monitoring appear to have no processes or procedures in place to audit this surveillance tactic, have no idea how often overt social media monitoring is being used nor are therefore able to assess whether it is being used in a way that is legitimate, necessary, proportionate and effective.

Whilst a few local authorities sought to estimate their usage, others said social media monitoring occurred on a daily basis and some said the information might be logged on the case file but not centrally so were not able to respond.

“Officers will view social media from time to time in the course of investigations, but these individual observations are not recorded other than in the prosecution file as part of disclosure procedure.”

Ashford Borough Council

East Dunbartonshire were able to offer figures and stated that their Corporate Fraud team had undertaken 105 social media inquiries since January 2017 which totalled 21 hours and 40 minutes. Rhondda Cynon Taff Council stated that in 2018-19 they conducted 9 investigations; in 2017-18 they conducted 29 investigations and in 2016-17 they conducted 55 investigations. These were either Human Rights Act, non-RIPA or single viewing of social media site investigations.

This lack of clear information indicates there is a risk that overt social media monitoring is being used by officials on an ad hoc basis without any assessment of whether it is effective and improves rather than undermines the quality of decision making.

Accountability and legitimacy

Whilst the approach, which results in different exploitation of individuals’ social media based on their privacy settings, is approved by the Investigatory Powers Commissioner, the regulator who oversees use of surveillance powers by public authorities in the United Kingdom, there has been a notable absence of public and parliamentary debate.

Key questions such as the legitimate aim of such activities and whether social media monitoring is necessary and proportionate in the different contexts it is being deployed by local authorities, have not been debated publicly, nor appear to have been considered at a local level in sufficient detail.

When decision making has serious consequences for an individual, this brings the added risk that comes from unequal access to data, unequal access to justice and the inability to challenge incorrect assumptions that influence or determine human decision making .

This failure to assess and audit the effectiveness of overt social media monitoring in intelligence gathering and investigations by local authorities, means local authorities do not assess how correct they are on deciding integrity of motive of an individual based on their social media output; and means they cannot judge whether they are adept in relation to new forms of online behaviour, norms and languages, which can make analysis and verification difficult.

This may become more pronounced if local authorities start using social media analytics tools in their investigations, rather than fraud investigators, for example, doing a manual check on someone’s Facebook posts.

These platforms retain otherwise fleeting and contextually limited content.

Daniel Trottier, European Journal of Cultural Studies 2015, Vol.18(4-5) 530-547

As acknowledged by Arun District Council in their guidance:

“In using information obtained from the Internet/social networks, it must be recognised that the ‘open source’ environment is by nature insecure. Information obtained cannot be assumed to be fact and should therefore be subject to separate confirmation. Ideally, additional corroborating evidence should be obtained from a more robust source.

As part of the investigation, consideration must also be given to the circumstances of the case and whether the information is, in fact, demonstrating inappropriate activity. (For example, Facebook postings could suggest that a ‘sick’ employee is engaging in activity that is inconsistent with their condition – however, without additional medical advice, or independent examination, this cannot be assumed as being the case). While such information may be introduced into investigative / disciplinary proceedings as potential evidence, it cannot on its own be deemed to be proof in support of an accusation.”

Despite not appearing to conduct social media monitoring, based on their FOIA response, Blackburn with Darwen Borough Council have a Procedural Guide which states that investigating officers “should use a process of monitoring what they do on social media right from the start of an investigation. This will assist them with the process of deciding whether or not they will need to complete a RIPA or non-RIPA form” and complete an internal log where they record:

- Reason/justification for the viewing;

- Assessment of the likelihood of accessing private information about individuals whether they are the target or other individuals;

- Date of viewing;

- Pages viewed;

- Pages saved and where saved to

- Private information gathered i.e. any information about an individual’s private and family life.

Whilst this appears to be an example of good practice in terms of authorisation, it is not clear whether there is a process to then audit these logs or whether these logs are used simply to decide whether “more investigation is required.”

Braintree District Council’s guidance also states that “Each viewing of an individual’s social network account must be recorded” although there is no indication that this is audited.

“If an allegation is received, or as part of an investigation into an individual, it is necessary to view their social networking site, officers may access the main page of the individual’s profile in order take an initial view as to whether there is any substance to the allegation or matter being investigated.

The viewing of an individual’s social network account must be reasonable and proportionate.

Each viewing of an individual’s social network account must be recorded.”

Braintree District Council

Bridgend County Council state they do use overt social media monitoring and that:

“Overt surveillance must be authorised by Legal Services and the appropriate Head of Service within the investigatory department.”

However, when asked whether they could state how regularly social media monitoring is used, they stated they did not hold this information. It is unclear that authorisation is recorded in any way.

Kingston also require ‘management approval’ before one-off viewing of social media, but they were unable to state how regularly they use social media monitoring, again indicating that approval may not be logged or reviewed.

It appears that even at those local authorities where there is a requirement to log activities or seek approval, there is no follow up which would identify poor practices or deficiencies in how overt social media is conducted and whether ‘intelligence’ gained is used effectively and properly.

4. Your social media profile could be used by a Local Authority, without your knowledge or awareness, in a wide variety of their functions, predominantly intelligence gathering and investigations.

We found that local authorities are using 'overt' social media monitoring in the following areas:

- Recovery of unpaid Council Tax arrears

- Debt recovery

- Regulatory Services/Trading standards e.g. allegation of advertising illegal goods

- Neighbourhood Services

- Licensing

- Corporate Anti-Fraud teams / Revenues and benefits

- Environmental investigations

- Children's social care

- Monitoring protests and demonstrations

Allderdale Borough Council’s 4-man debt recovery team use social media for recovery of unpaid Council Tax arrears and states that:

“…the debt recovery department occasionally checks employment details by a number of different sources (which may include social media). This is done overtly and is therefore not subject to RIPA.”

Overt in this case involves “officers carry out a quick check on Facebook to see if the debtor has stated their employer on there.”

However, they state that in order for this to be done:

“A Liability Order has been granted against the debtor by West Allerdale Magistrates Court, and that they still have arrears outstanding, and also that they have refused to answer the question on our questionnaire which asks them to notify us where they work, so we can do an attachment of earnings.”

Barnet London Borough Council state that:

“Officers in Regulatory Services may do an initial one-off check on social media when considering the validity of an allegation that someone is for example advertising illegal goods, but would not repeatedly search social media as officers are aware of the need to consider a RIPA application for directed surveillance.

Licensing would conduct a “one time only” visit to the relevant social media page with a view to collecting evidence for a specified investigation. They would only use it to assist in an investigation if relevant and do not use it for monitoring purposes.”

Cambridge County Council use overt social media monitoring in a number of investigations:

The Council does make use of overt social media intelligence in the course of some investigations (fraud, environmental investigations such as fly-tipping, enforcement of licensed activities such as tattooing).

Cheshire East Council include children’s social care:

Trading standards; regulatory and environmental health services, communications team, children’s social care.

Leicestershire County Council also focus on children’s services:

Social media monitoring is also being considered for the Safeguarding area within Children’s services. However, this is in the early stages of development and, as yet, we don’t have any firm dates for implementation.

Cheshire West informed us that they are likely to expand use of overt social media monitoring:

While access to individual’s SNS by Council Officers has largely been confined to those undertaking official investigations, for example Trading Standards Officers or members of the Fraud and Investigations team, those activities would be closely supervised, there is growing awareness that a number of other roles, most notably those relating to care of children and vulnerable adults and Council Tax/Benefits, may also view SNS as a legitimate information resources.

Kingston discuss use by their community housing team:

The council’s Anti-Fraud Team uses social media intelligence for conducting investigations…The council’s Community Housing Team use it for investigations that could include reference to public domain data.

Oldham Council use social media monitoring in relation to protests and demonstrations and to identify a groups’ activities:

The Council monitors social media to gather intelligence about community tensions. This would include for example, finding out about a group’s plans to hold protests or demonstrations. All material accessed is open source. Identification of groups’ activities would only be identified because they are publicly stating what they plan to do.

Swindon Borough Council, Internal Audit Services: Use of Social Media for Investigations policy identifies use in relation to homelessness applicants:

“Officers in Housing, Homelessness and Children’s Services informed the Auditor that they or their staff use social media to gather information on clients. For example, homelessness applicant’s Facebook profiles (open source) may be viewed to confirm whether information provided by them is true e.g. where they previously lived. In Children’s Services, Social Workers may view the Facebook profiles of parents to establish whether they have broken any agreements between them and the Council e.g. for two parents not to have contact with one another.

…The Council doesn’t have a policy that covers the use of social media to gather or verify service users’ information, to ensure that an assessment of proportionality with regard to their right to privacy is carried out.

The various use cases outlined above should be seen as part of a broader apparatus being deployed, where social media monitoring plays a role. Privacy International’s work ‘When Big Brother Pays Your Benefits ’ examines the use of technology as a magic cure-all to socio-economic and political issues.

Newly established or reformed social protection programmes have gradually become founded and reliant on the collection and processing of vast amounts of personal data and increasingly the models for decision-making include data exploitation and components of automated decision-making and profiling.

Whilst social media monitoring by local authorities in the UK, at present, involves a manual check of individuals social media such as their Facebook page, as the use of such monitoring increases and is used in a wide variety of areas in which local authorities are active, so too will the prospect of automating such checks and monitoring. In turn, such practices lead invariably to automated decision-making, profiling and the inherent risks of such practices. This will be at the cost of individuals privacy, dignity and autonomy.

Therefore, is it vital that the collection and processing of personal data obtained from social media as part of local authority investigations and intelligence gathering, are strictly necessary and proportionate to make a fair assessment of an individual. There needs to be effective oversight of use of social media monitoring both overt and covert to ensure that particular groups of people are not disproportionately affected, and where violations of guidance and policies do occur, they are effectively investigated and sanctioned.

We further note that for example Oldham Council uses social media monitoring in relation to protests and demonstrations and to identify a groups’ activities. The unregulated use of social media monitoring negatively affects the right of freedom of peaceful assembly. It has a chilling effect on individuals wishing to organise online, as well as using social media platforms to organise and promote peaceful assemblies.

RECOMMENDATIONS

To the Investigatory Powers Commissioner:

- Call for guidance setting out guidelines, with concrete examples, by which local authorities may assess:

- What constitutes a legitimate aim for local authorities to rely on in order to conduct overt social media monitoring;

- In what circumstances overt social media monitoring is just and proportionate to these legitimate aims;

- Whether repeated or persistent viewing constitutes directed surveillance.

To the local authorities:

- Local authorities should refrain from using social media monitoring, and should avoid it entirely where they do not have a clear, publicly accessible policy regulating this activity

Where exceptionally used:

- Every time a local authority employee views a social media platform, this is recorded in an internal log including, but not limited to, the following information:

- Date/time of viewing, including duration of viewing of a single page

- Reason/justification for viewing and/or relevance to internal investigation

- Information obtained from social platform

- Why it was considered that the viewing was necessary

- Pages saved and where saved to

- Local authorities should develop internal policies creating audit mechanisms, including:

- The availability of a designated staff member to address queries regarding the prospective use of social media monitoring, as well as her/his contact details;

- A designated officer to review the internal log at regular intervals, with the power to issue internal recommendations

RIPA is the law governing the use of covert techniques by public authorities. It requires that when public authorities, such as local authorities, need to use cover techniques to obtain private information about someone, they do it in a way that is necessary, proportionate, and compatible with human rights.

RIPA’s guidelines and codes apply to actions including covert social media monitoring. Local authorities in the UK have a wide range of functions and are responsible in law for enforcing over 100 separate Act of Parliament.

In particular local authorities investigate in the following areas: trading standards, environmental health, benefit fraud. As part of their investigation a local authority may consider that it is appropriate to use a RIPA technique to obtain evidence. From 1 November 2012 local authorities are required to obtain judicial approval prior to using covert techniques. https://www.gov.uk/guidance/surveillance-and-counter-terrorism

RIPA use requires the internal approval of an Authorising Officer but also that of a magistrate.

SUMMARY

INTRODUCTION

- Privacy Settings

- What is repeated viewing

- Accountability and legitimacy

- Data integrity

- Reframing social media platforms, users and data in terms of intelligence gathering and criminality

- The future

FINDINGS

ANALYSIS OF FINDINGS

- A significant number of local authorities are now using 'overt' social media monitoring and this substantially out-paces the use of 'covert' social media monitoring

- If you don't have good privacy settings, your data is fair game for overt social media monitoring.

- There is no quality check on the effectiveness of this form of surveillance on decision making

- Your social media profile could be used by a Local Authority, without your knowledge or awareness, in a wide variety of their functions, predominantly intelligence gathering and investigations.

RECOMMENDATIONS

To the Investigatory Powers Commissioner:

- The IPCO should call for guidance setting out guidelines, with concrete examples, by which local authorities may assess:

- What constitutes a legitimate aim for local authorities to rely on in order to conduct overt social media monitoring

- In what circumstances overt social media monitoring is just and proportionate to these legitimate aims

- Whether repeated or persistent viewing constitutes directed surveillance

To the local authorities:

- Local Authorities should refrain from using social media monitoring, and should avoid it entirely where they do not have a clear, publicly accessible policy regulating this activity

Where exceptionally used:

- Local authorities should use social media monitoring only if and when in compliance with their legal obligations, including data protection and human rights.

- Every time a local authority employee views a social media platform, this should be recorded in an internal log including, but not limited to, the following information:

- Date/time of viewing, including duration of viewing of a single page

- Reason/justification for viewing and/or relevance to internal investigation

- Information obtained from social platform

- Why it was considered that the viewing was necessary

- Pages saved and where saved to

- Local authorities should develop internal policies creating audit mechanisms, including:

- The availability of a designated staff member to address queries regarding the prospective use of social media monitoring, as well as her/his contact details;

- A designated officer to review the internal log at regular intervals, with the power to issue internal recommendations