Texas Media Company Hired By Trump Created Kenyan President's Viral 'Anonymous' Attack Campaign Against Rival, New Investigation Reveals

The battle for Kenyan voters’ allegiance in the 2017 Presidential election was fought on social media and the blogosphere. Paid advertisements for two mysterious, anonymous sites in particular started to dominate Google searches for dozens of election-related terms in the months leading up to the vote. All linked back to either “The Real Raila”, a virulent attack campaign against presidential hopeful Raila Odinga, or Uhuru for Us, a site showcasing President Uhuru Kenyatta’s accomplishments. As ads for the two sites flooded Twitter, Facebook and YouTube accounts across the country, Kenyans speculated that British data analytics firm Cambridge Analytica had fronted them. The company has previously been reported to be working for the President. It was clear that whoever sponsored them had a lot of money to spend.

The two online campaigns were actually created by Harris Media LLC, a far-right American digital media company, on behalf of President Kenyatta’s re-election campaign, Privacy International can reveal. Harris Media are a digital advertising and creative agency for primarily political clients. Harris Media uses data analytics to create political campaigns that target audiences using information gleaned from how people use their social media accounts. Its previous clients include the Trump campaign and several far-right European parties.

Harris Media’s Real Raila and Uhuru for Us campaigns relied on ad words in Google search and apparently targeted advertising on a range of social media platforms. This raises serious concerns about the role and responsibility of companies working for political campaigns in Kenya’s volatile political climate, particularly considering The Real Raila’s incendiary claims include that rival opposition candidate Raila Odinga’s administration would “remove whole tribes”, for example. It also highlights the risks inherent to voter profiling and micro-targeting in a country with no data protection laws.

A data-driven dirty campaign

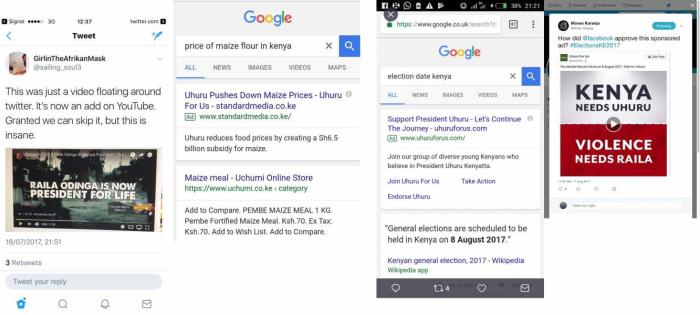

[Paid advertisements for the Real Raila and Uhuru for Us. Obtained by Privacy International.]

The way in which data is used in elections and political campaigns is highly privacy invasive, raises important security questions, and has the potential to undermine faith in the democratic process. However, data-driven campaigning is nothing new. For decades, campaigns have been using and refining targeting, looking at past voting histories, demographic and other information to understand voters’ issues and values, mirroring tactics long used by marketers and commercial advertisers.

What is new, however, is the granularity of data that is available to campaigns. Data brokers and data analysis companies collect or obtain data about you, for example, your browsing history, your location data, who your friends are, or how frequently you charge your battery, and then use these data to infer additional, unknown information about you, like your next purchase, your gender, your personality, your preferred candidate, your emotional state, your sexual orientation, etc. This is then used to create a profile of you. The profile is used to selectively target custom audiences with shiny, sometimes bespoke political ads.

[Targeted advertising and Google Adwords are central to Harris Media’s campaigns.]

This is a major part of Harris Media’s business model. “Facebook ads allow you to identify and target people who are in 100% agreement with your values system”, founder Vincent Harris in a post from 2010 about targeted advertising, discussing recent work. “[Facebook’s] functionality, and organic user base make its usage far more beneficial than spending time and money having to cultivate support on a unique platform.” Geo-tagging, re-tagging, behavioural targeting, demographic targeting, voter file targeting, individual targeting by email address and cookie targeting: all are strategies Harris promoted in a 2014 reflection on digital campaigns.

Another tactic is the judicious use of Google Adwords. This explains why paid-for ads for The Real Raila and Uhuru For Us emerged above the search results for many Kenyan election-related search terms. As of 2015, an advertiser could use personal information held by them, such as email addresses, to target customers using Google’s ad service. Facebook, Twitter, and Google do not just facilitate ‘better’ targeting. They also actively shape campaign communication through their close collaboration with political staffers, according to one academic study. The recent scandal over alleged Russian government interference in the 2016 US presidential race on social media has prompted calls for the regulation of micro-targeting practices.

In a campaign for the far-right Alternative for Germany party, Harris Media reportedly created target groups for anti-immigrant messages including mothers, business owners and working-class people using the “lookalike audience” feature of Facebook. How it works: an advertiser creates a pre-identified “custom audience” of individuals that the advertiser wants to target with its messages using data in its possession, like customer and prospect lists, people who have visited the advertiser’s website or app, or people who have interacted with its Facebook Page or adverts. By analysing shared interests and demographic details of this “custom audience”, Facebook generates a new list of Facebook users for the advertiser who share the custom audience’s attributes – the lookalike audience.

How was targeting done for Harris Media’s Kenyan campaigns, and using what data? Did some of these groups include tribal affiliation or other politically sensitive criteria? The fact that we cannot (currently) answer these questions – and that we do not know if and how these specific ads were targeted - raises serious concerns about accountability and transparency. It leaves unanswered important questions as to how such data will be stored, who will have access to it, and what it will be used for.

Harris’ campaigns for the President landed at a time Kenya was experiencing widespread media suppression and intimidation, the brutal murder of a key electoral official, and tit-for-tat accusations of hate speech by Kenyatta’s team and Odinga himself. By July, the country’s National Integration and Cohesion Commission and electoral observers warned of “a serious risk of violence”. And with reason. At least 33 people were killed in Nairobi alone following the August 8 election, most of them as a result of action by the police, according to Human Rights Watch.

Harris Media publicly claims much of its political campaign work – even for controversial international clients like the extreme right AfD (Germany) and the Front National (France), and Israel’s Likud government. Kenya, however, was not one they were eager to claim. Yet the digital trail from both of the Kenyan digital campaigns leads firmly back to the Austin, Texas outfit.

The Real Raila and another site which links back to Uhuru for Us, Candidates for Kenya, share an IP address with Harris Media’s own website and over 30 conservative campaigns. These include the websites for the Republican Party of Texas, pro-fracking and oil industry lobbies, and a Benghazi attack conspiracy theory site, among others. The Real Raila’s Google Analytics tag (UA-46042337), is shared with several known Harris Media campaigns. A tag is a piece of data-collecting code assigned to a website by its creator to collect visitor behaviour information. The Uhuru for Us site (UA-51987218) also shares its tag with 39 other conservative websites, several of which are publicly attributed to Harris Media.

Three Harris Media staff, including Josh Canter, its vice president for content production, an account director, and a designer worked on The Real Raila site, authoring blog content, mostly republishing lightly-sourced characterisations of Odinga as a dangerous, racist xenophobe with promoting his tribe and family as his primary political aim. The Uhuru For Us Twitter account still appears linked to a Harris Media email address. Created in March 2017, its first follower was Kenyatta’s Digital Media Strategist.

Harris Media did not respond to requests for comment on the company’s work in Kenya. Senior Harris Media staff have informally publicly discussed work for President Kenyatta, according to two independent sources. Secretary-General of the President’s Jubilee Party, Raphael Tuju, claims no knowledge of the Real Raila site.

Playing with fire

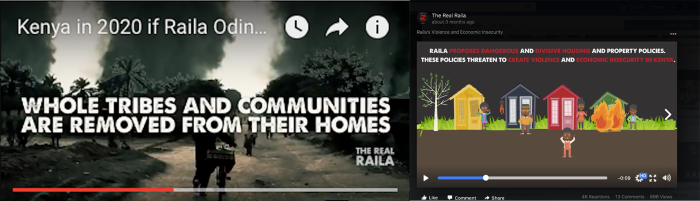

A little man, panicked, runs across the screen. The houses behind him burn. This is the future with an Odinga presidency, declared a video posted to The Real Raila Facebook page on 24 July.

[Campaign material produced by Harris Media for the President’s campaign channels Kenya’s recent history of ethnic violence to accentuate fears over the possible election of his rival.]

This choice of imagery is not an accident. It is an explicit reference to Kenya’s violent past. In the months leading up to the election, many Kenyans feared a repeat of the post-election violence of 2007-2008, when widespread dissatisfaction over the result erupted as extreme violence expressed often in ‘tribal’ language and targeting. At least 1,100 people were killed and thousands forced to flee their homes. Since 2008, the production and dissemination of hate speech – “threatening, abusive or insulting [language], words or behaviour” marked by an intent to “stir up ethnic hatred, or having regard to all the circumstances, ethnic hatred is likely to be stirred up” – is illegal. For this election cycle, the Communications Authority issued controversial guidelines to prevent ‘undesirable political messages’. But anonymous statements on social media platforms – where Kenyatta’s and Odinga’s campaigns targeted voters – are much harder to track.

Privacy International asked the National Integration and Cohesion Commission Commissioner Dr. Joseph Nasongo whether specific examples from the Real Raila campaign would constitute hate speech or incitement, he called it “a grey area” of speech. Unless a specific group or protected category is mentioned in the utterance or statement in question, a court would generally not consider it to be incitement or hate speech, Nasongo explained. If the statement about “whole tribes” being removed had referred to the strongly Jubilee-supporting Kikuyu directly as the group that an Odinga government would “remove” (the subtext is based on a June statement by Odinga, for which he was investigated) then there could be a case for considering such speech incitement. The Real Raila campaign avoids expressly ethnic references. But it does reprint statements sourced elsewhere containing these, and also contains coded political language which indirectly highlights existing ethnic tensions. “The communities who are listening to such coded [language], they know exactly what someone is saying,” Nasongo explains. Hate speech or not, such coded language creates fear – and that has consequences at the ballot box.

The lack of transparency over the financing of Real Raila and Uhuru for Us ads, too, prevents effective probing of how they spread and the analysis of personal data driving it. Kenyan electoral laws and regulations also do not clearly require candidates to endorse campaigns or ads that they have funded, and the Real Raila and Uhuru for Us campaigns are attributed to “young Kenyans” and “concerned Kenyans for peace”. This has serious implications for democracy and Kenya’s national unity, which appears increasingly fragile. Grace Mutungu studies internet governance as a Harvard University fellow. She attributes much of the surprising viral success of the “below the belt” campaign to its dissemination on WhatsApp and social media platforms.

But are these data-driven social media campaign just politics as usual? “That may be the way politics is run in many places in the world,” believes Mutungu. “But in Kenya, there are so many things that are like open wounds… So when you put out a video that gives such an extreme view, it doesn’t help in building the country. It helps in perpetuating polarization.”

Making it reign

The use of targeted political ads online is under increasing scrutiny. For example, executives from tech giants Google, Facebook and Twitter recently testified about how their platforms came to host political content allegedly paid for by Russian agents during the 2016 US Presidential campaign.

Cambridge Analytica, a British data analytics firm, also has serious questions to answer about its work in Kenya, which was first reported last May. Both Cambridge Analytica and Harris Media have a history of clients in common including US President Donald Trump and Senator Ted Cruz. And like Harris Media, Cambridge Analytica was also discretely working for the President in the same time period, Privacy International can confirm. It gathered survey data on Kenyans to aid the campaign and managed the president’s image, according to current and former company employees speaking to Privacy International. It is not alleged here that Cambridge Analytica was involved in Harris Media’s campaigns for Kenyatta. A company spokesperson for Cambridge Analytica stated that Cambridge Analytica has no relationship with Harris Media or the ‘Real Raila’ or ‘Uhuru for Us’ campaigns, adding that Cambridge Analytica was not involved in any negative political content in Kenya.

At least three Cambridge Analytica employees – its Creative Director, and two web and software developers – managed the Jubilee Party’s website. Two employees had active log in credentials to the site as late as October 2017. Several further employees were based in and travelled to Nairobi in late 2016 and throughout 2017. Alexandra Phillips, former head of media for the UK Independence Party, was employed by Cambridge Analytica to brief media on behalf of Kenyatta, in a document seen by Privacy International. Phillips denied working for Jubilee, even after publishing photos on Instagram of her with the Jubilee team. Nevertheless, an employee at Cambridge Analytica speaking to Privacy International confirmed that Phillips had worked for the company. A company spokesperson denies this. Kenyan government officials have denied Cambridge Analytica ever worked for the President.

Murkier, however, is the survey work Cambridge Analytica carried out in Kenya, according to two independent sources familiar with the company. This is problematic because Kenya has no data protection law, meaning there is potentially disproportionate amounts Kenyans’ data being collected, shared and further processed without being subject to any regulations and independent oversight, which is particularly concerning for what is qualified as sensitive personal data such as sex, ethnicity, religion and political affiliation.

Cambridge Analytica is being probed by the UK Information Commissioner’s Office for potential misuse of personal data. In the US, the company was reportedly scrutinized by the US House of Representatives Permanent Select Committee on Intelligence over its work for President Trump’s campaign in 2016. The fact of these investigations does not inspire confidence that Cambridge Analytica behaved ethically in its collection and use of Kenyans’ personal data to benefit their Presidential client. Privacy International previously wrote to the company requesting clarification; we have not received a response.

Thinking twice

Kenyatta was re-elected as Kenya’s President in second presidential election held in October. He presides over a bitterly divided country. The data-driven Real Raila campaign, in particular, certainly did not help. “Social media platforms have never been about democratization or free speech,” wrote Vincent Harris from 2010. “Direct media is dead and has been replaced by a censored, suppressed, and curated media.” If the millions of dollars that political campaigns are willing to spend globally to target their messages to a tracked audience are any indication, then the content of those messages matters. Such tactics require transparency, especially in as polarised and tense a society as Kenya. “Even at the point of casting a vote,” says Dr. Nasongo, “the voter will think twice, with those images engrained in his or her mind.”