Search

Content type: News & Analysis

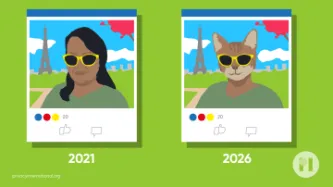

The notorious Clearview AI first rose to prominence in January 2020, following a New York Times report. Put simply, Clearview AI is a facial recognition company that uses an “automated image scraper”, a tool that searches the web and collects any images that it detects as containing human faces. All these faces are then run through its proprietary facial recognition software, to build a gigantic biometrics database.

What this means is that without your knowledge, your face could be stored…

Content type: News & Analysis

What if we told you that every photo of you, your family, and your friends posted on your social media or even your blog could be copied and saved indefinitely in a database with billions of images of other people, by a company you've never heard of? And what if we told you that this mass surveillance database was pitched to law enforcement and private companies across the world?

This is more or less the business model and aspiration of Clearview AI, a company that only received worldwide…

Content type: Video

<br />

Links

Read more about the ICO's provisional decision

Support our work

You can find out more about Clearview by listening to our podcast: The end of privacy? The spread of facial recognition

Content type: Press release

In what could be seen as one of the strongest sanctions against the company in Europe, the Information Commissioner’s Office (ICO), which is tasked with enforcing data protection legislation in the UK, has today announced its provisional intent to issue a potential fine of £17 million against the controversial facial recognition company Clearview AI.

Clearview AI, which only received worldwide attention following a New York Times report back in January 2020, is a company whose business model…

Content type: Advocacy

The Office of the Privacy Commissioner of Canada has developed draft privacy guidance for police agencies' use of FRT, with a view to ensuring any use of FRT "complies with the law, minimizes privacy risks, and respects privacy rights". The Commissioner is undergoing consultation in relation to this guidance.

Privacy International and the Canadian Civil Liberties Association ("CCLA") welcome the Commissioner's efforts to strengthen the framework around police use of facial recognition, and the…

Content type: Examples

The Myanmar military are stopping people in the street, checking through the data on their phones, and taking them to jail if they find suspicious messages or photos. At least 5,100 people were still in jail many months after opposing the February 1, 2021 military takeover. The spontaneous searches also deter individuals from continuing to post on social media or lead them to create new accounts they hope will evade detection, and avoid crowded streets where police or soldiers are likely to be…

Content type: Examples

July 2021 saw violent protests that left 72 people dead and 1,300 in prison after former president Jacob Zuma was jailed for failing to appear before a constitutional court’s inquiry into corruption during his time in office. In response, the South African government deployed the military onto the streets in the provinces of Gauteng and Kwazulu Natal, and began monitoring social media platforms and tracking those who “are sharing false information and calling for civil disobedience”. President…

Content type: Examples

The South African government urged social media platforms to trace and remove posts that incite violence, share false information, and call for civil disobedience after a July 2021 series of spiralling protests sparked by the jailing of former president Jacob Zuka. A number of other African countries such as eSwatini, Senegal, Nigeria, Uganda, Niger, and the DRC have also been increasingly using tracking software, internet shutdowns, and social media monitoring during protests and elections.…

Content type: News & Analysis

After almost 20 years of presence of the Allied Forces in Afghanistan, the United States and the Taliban signed an agreement in February 2020 on the withdrawal of international forces from Afghanistan by May 2021. A few weeks before the final US troops were due to leave Afghanistan, the Taliban had already taken control of various main cities. They took over the capital, Kabul, on 15 August 2021, and on the same day the President of Afghanistan left the country.As seen before with regime…

Content type: Examples

While traditional media sought to criminalize the widespread November 2020 protests in Peru following the Congressional ouster of President Vizcarra, witnesses disseminated videos and photographs of police abuse on social networks. In the fear and uncertainty, many myths also circulated. In Peru, citizens have the right to refuse to allow police to check their cellphones unless they have a court order; slowed or absent wireless connections may simply be due to overload; as public officials,…

Content type: Examples

As police began treating every 2019 Hong Kong protest as an illegal assembly attracting sentences of up to ten years in jail, facial recognition offered increased risk of being on the streets, as protesters could be identified and arrested later even if they were in too large a crowd to be picked up at the time. By October, more than 2,000 people had been arrested, and countless others had been targeted with violence, doxxing, and online harassment. On the street, protesters began using…

Content type: Examples

Both protesters and police during the 2019 Hong Kong protests used technical tools including facial recognition to counter each other's tactics. Police tracked protest leaders online and sought to gain access to their phones on a set of Telegram channels. When police stopped wearing identification badges, protesters began to expose their identities online on another. The removal of identification badges has led many to suspect that surveillance techniques are being brought in from mainland…

Content type: Examples

On November 9, 2020, after a year of escalating tensions, Peruvian president Martín Vizcarra was impeached on the grounds of "moral incapacity" by lawmakers threatened by his anti-corruption investigations and the policy reform he led. The street protests that followed all over the country were coordinated via Instagram, Twitter, WhatsApp, and TikTok (#MerinoNoMeRepresenta) by hundreds of newly-created small, decentralised organisations. The march on November 14 is thought to be the largest in…

Content type: Examples

Protesters in Tunisia have faced hate messages, threats, and other types of harassment on social media, and been arrested when they complain to police. Arrests and prosecutions based on Facebook posts are becoming more frequent, and in street protests law enforcement appears to target LGBTQ community members for mistreament. In a report, Human Rights Watch collected testimonies to document dozens of cases in which LGBTQ people were harassed online, doxxed, and forcibly outed; some have been…

Content type: Examples

Documents acquired under the Government Information (Public Access) Act 2009 reveal that staff and student protests against cuts at the University of Sydney were surveilled by both the university administration and police, who have been widely criticised for using excessive force at education protests. The university administration conducted "risk reviews" of protests and looked for links between education protest organisers and other political organisations. Emails include screenshots of…

Content type: Examples

Despite having promised in 2016 not to facilitate domestic surveillance, the AI startup Dataminr used its firehose access to Twitter to alert law enforcement to social media posts with the latest whereabouts and actions of demonstrators involved in the protests following the killing of George Floyd. Dataminr's investors include the CIA and, previously, Twitter itself. Twitter's terms of service ban software developers from tracking or monitoring protest events. Some alerts were sourced from…

Content type: Examples

Peruvian police have used force, arbitrary arrests, undercover infiltrators, tear gas, and forced disappearance against marchers protesting the removal of president Martín Vizcarra. Three protesters have been killed, more than 60 have disappeared, and hundreds have been injured. While the traditional media has either ignored the protests or depicted them as criminal, social media and the internet have been crucial in documenting police abuses via shared images and video. Police have begun using…

Content type: Examples

During the Black Lives Matter protests of summer 2020, US police took advantage of a lack of regulation and new technologies to expand the scope of people and platforms they monitor; details typically emerge through lawsuits, public records disclosures, and stories released by police department PR as crime prevention successes. A report from the Brennan Center for Justice highlights New York Police Department threats to privacy, freedom of expression, and due process and the use of a predator…

Content type: Press release

Privacy International (PI), together with Hermes Center for Transparency and Digital Human Rights, Homo Digitalis and noyb - the European Center for Digital Rights, has today filed a series of legal complaints against Clearview AI, Inc. The facial recognition company claims to have “the largest known database of 3+ billion facial images”. The complaints were submitted to data protection regulators in France, Austria, Italy, Greece and the United Kingdom.

As our complaints detail, Clearview AI…

Content type: Explainer

What is social media monitoring?

Social media monitoring refers to the monitoring, gathering and analysis of information shared on social media platforms, such as Facebook, Twitter, Instagram and Reddit.

It may include snooping on content posted to public or private groups or pages. It may also involve “scraping” – grabbing all the data from a social media platform, including content you post and data about your behaviour (such as what you like and share).

Through scraping and other tools…

Content type: Advocacy

This report is presented by TEDIC (Technology and Community Association) and Privacy International (PI). TEDIC is a non-governmental, non-profit organization, based in Asunción, that promotes and defends human rights on the Internet and extends its networking to Latin America. PI is a London based human rights organization that works globally at the intersection of modern technologies and rights.

TEDIC and PI wish to express some concerns about the protection and promotion of the right to…