Statement before the European Parliament hearing on "Spyware used in third countries and implications for EU foreign relations"

On 15 December 2022, PI gave evidence for a third time before the EP Committee of Inquiry to investigate the use of Pegasus and equivalent surveillance spyware [PEGA Committee].

PI Opening Statement at PEGA Hearing on "Spyware used in third countries and implications for EU foreign relations"

Thank you very much for offering me the opportunity to give evidence before this Committee for another time on behalf of Privacy International (or PI) – a London-based non-profit that researches and advocates globally against government and corporate abuses of data and technology.

My opening statement will first briefly touch on the EU foreign policy’s priorities. I will then focus on EU’s role in tranferring surveillance capabilities to third countries. I will there outline our concerns and observations regarding those trasfers and conclude with key recommendations by PI that seek to assist this Committee in strengthening the rule of law and upholding the rights of millions of individuals living in the EU and beyond.

Respect for human rights and dignity – together with the principles of freedom, democracy, equality and the rule of law – are values common to all European Union (EU) countries. They also guide the EU’s action both inside and outside its borders.

The European Union’s global strategy for foreign and security policy has set out five broad priorities, among which there is a commitment to “Rules-based global governance”. In particular, “the EU is committed to a global order based on international law, which ensures human rights…”. The common policy commits to systematically mainstreaming human rights and gender issues across policy sectors and institutions “and to champion their indivisibility and universality.”

This commitment underpins every activity including the security and defence priorities, where the EU has committed to “develop human rights-compliant anti-terrorism cooperation with [among others] North Africa, the Middle East, the Western Balkans and Turkey”.

The EU foreign policy plays a key role in supporting the rule of law, democratisation, and human rights protection around the world. Yet we are concerned that certain EU practices seem to undermine the same core rules and values they have committed to promote and champion.

Specifically, we are gravely concerned about the activities carried out by the European Commission, as well as, most notably, the European Border and Coast Guard Agency (Frontex), the European Union Agency for Law Enforcement Training (CEPOL) and the European External Action Service (EEAS), which relate to the transfer of surveillance capabilities to authorities of non-EU countries.

This surveillance support from several EU bodies and institutions includes direct transfer of surveillance equipment to third countries; training of third country intelligence and security forces; financing of their operations and procurement; facilitating of exports of surveillance equipment by industry and promoting legislation which enables surveillance.

These transfers include transfers of spyware and hacking capabilities, which can be used not only against human rights defenders, journalists, and others, but across borders against people in EU countries as well as EU diplomats.

We know this as a result of a long and extensive access to documents process that Privacy International has undertaken since 2019. These documents reveal a far more worrying picture of what the EU institutions and its member-states contribute to.

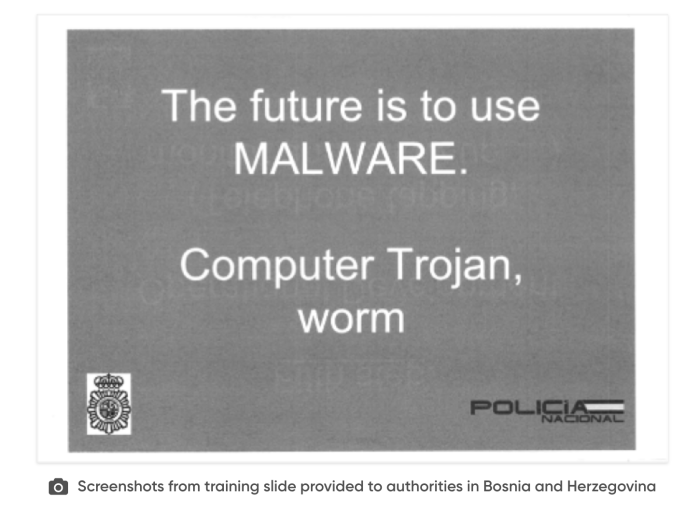

For example, documentation of a training session provided by the national police force of Spain with EU support, to the police, security, and intelligence authorities in Bosnia and Herzegovina on financial investigations revealed the promotion of the use of malware or computer trojans – that is software used to hack into devices to extract data and take control of functions such as the camera and microphone, and that is sold on the open market by companies such as NSO Group.

The European Union is the world’s largest donor of development aid, an instrumental supporter of democracies and peace around the world, and a powerful global force for reigning-in big tech and other exploitative industries. However, in the past years they have been using those powers to expand the surveillance capabilities of neighboring countries and beyond.

Just two examples:

Among others, the EU Trust Fund for Africa, a funding programme which uses EU aid money for migration control, has provided the government of Niger with surveillance equipment that includes a cellphone tower simulator used to intercept communications – this is often referred to as an IMSI catcher. They are highly intrusive devices designed to imitate mobile phone towers and capable of carrying out indiscriminate monitoring of mobile phones present in a given area. This allows otherwise anonymous people to be identified, and their locations to be tracked.

Yet, the country has no laws that regulate the use of this kind of intrusive equipment. There seem to be no robust restraints that can prevent authorities from using the equipment for other purposes – beyond just surveillance for border control purposes. The €11.5 million fund to Niger further included the provision of surveillance drones, surveillance cameras, surveillance software, and a wiretapping centre.

Similarly, in Serbia, security authorities have sought using EU funds to purchase tools used to gather personal data from Facebook, access user passwords, browsing history, contacts, location history, email, and quote “bypass 2-factor authentication” – a key security measure which activists, journalists and other rely upon around the world.

Last week the European Ombudsman agreed with our concerns. She issued a decision following a complaint submitted by Privacy International together with five other human rights groups, finding that the European Commission failed to take necessary measures to ensure the protection of human rights in the transfers of technology with potential surveillance capacity – supported by its multi-billion Emergency Trust Fund for Africa.

The Ombudsman’s inquiry investigated the support of projects across Africa that aimed at bolstering surveillance and tracking powers and involved extensive evidence-gathering from the Commission and complainants. It found that “the Commission was not able to demonstrate that the measures in place ensured a coherent and structured approach to assessing the human rights impacts”.

The decision recommends that the Commission now require that an “assessment of the potential human rights impact of projects be presented together with corresponding mitigation measures.”

The lack of such protections, which the Ombudsman called a “serious shortcoming”, poses a clear risk that these surveillance transfers might cause serious violations of human rights.

PI and the coalition of human rights groups have also filed two more complaints to the European Ombudsman on Frontex and the European External Action Service. The complaints are currently being similarly investigated.

Examples like the ones above underpin the threats these abuses pose for the rights of EU citizens too, as they can be exploited by third country authorities that lack the stringent safeguards present in the EU legal order.

The EU foreign policy plays a key role in supporting the rule of law, democratisation, and human rights protection around the world. It should take measures to ensure that its current activities do not undermine the same principles they seek to promote.

This Inquiry will by now be aware that the surveillance market is global, and that countries such as China, Israel and the US are all significant exporters and similarly provide financial and technical support to national authorities around the world for surveillance. There is no shortage of surveillance, which means that the work of activists and journalists in countries around the EU’s neighborhood will continue to be endangered, undermining democratisation efforts and entrenching authoritarianism – the very things the EU stands against, and which threaten its own economic and security interests.

We strongly believe that this Committee’s work can be central in ensuring that EU foreign relations are not undermined by spyware and other surveillance used in third countries.

With regard to what the EU should do, there are the following recommendations that we urge you to adopt.

- First, the export and transfer of certain surveillance technologies should be prohibited due to their highly intrusive nature and the unique threats they pose to privacy and security. Among others, hacking capabilities – sold by spyware companies such as the NSO Group – have the potential to be far more intrusive than any other surveillance technique, permitting the government to remotely and in secret access personal devices and all the intimate information they store. As such it is difficult to forsee a circumstance where their use would meet the standards and requirements set under international human rights law.

- Second, transfer of surveillance should be made conditional to an appropriate legal framework and effective safeguards – including independent authorisation and oversight procedures, as well as appropriate remedial mechanisms. Furthermore, support of surveillance technologies should only be provided to countries with adequate level of data protection frameworks.

- Third, any transfer of surveillance capabilities should be provided only after adequate human rights impact and risk assessments are carried out.

- Finally, it is key to provide the European Parliament greater capabilities of scrutiny and ensuring accountability over EU funds.

In sum, PI believes that this Committee is presented with a unique opportunity to uphold the fundamental rights of millions of people, while in doing so also promote the EU’s own interests. We are confident that it will live up to its challenging task and promote democracies, where people are free to be human both offline and online.

Thank you for your attention and I look forward to your questions.

Ilia Siatitsa

Programme Director and Senior Legal Officer