How the UK Conservative Leadership Race is Latest Example of Political Data Exploitation

The UK public, regulators, and parliamentarians have all expressed concern about the wide use of third-party data by all political parties in the UK and its impact on privacy and democracy. In the week the remaining six candidates to be the UK’s next Prime Minister are reduced to two, Privacy International takes a look at their privacy policies to illustrate how such policies can be used to identify the use of third-party data by political candidates from all political parties.

The race to become the next leader of the UK’s Conservative Party – and the next Prime Minister of the UK – is entering a crucial week, which will result in Conservative MPs voting only two of the remaining six candidates through to a final vote by the Conservative Party’s 160,000-strong membership.

Although the UK electorate-at-large is not being asked to decide, the candidates have all established formal campaigns aimed at securing the necessary votes, including through the use of third-party data to coordinate and promote their campaigns. Political data exploitation is big business: today, companies sell a wide range of services used by campaigns, ranging from data analytics used to decide which campaign messages to promote in each area, to deciding how to target supporters and people 'like' them.

Inevitably, this raises a large range of privacy concerns, including the threat that candidates amass large and intrusive personal datasets about people to be used for various purposes, including profiling and targeted advertising. In today’s era of digital campaigning, this is often done without people’s knowledge and consent and facilitated by the exploitation of data from a range of commercial sources such as data brokers and social media.

While political campaigning has always involved the utilisation of as much information as possible, the recent exploitation of digital data by campaigns around the world - including during the Brexit campaigns – has demonstrated the hidden and unaccountable nature of many of the current players involved, which represent a real threat to democracy itself.

One of the most crucial ways this can be checked is through strong and properly enforced privacy and data protection rules. In the EU, this includes the principle of Transparency, which is in part given effect through individuals’ right to information about how their data will be used.

This is what’s known as an ‘ex ante’ safeguard, meaning that as a minimum this information should be articulated in an information notice - often the candidates’ privacy policies. Among other things, such policies must include how data is collected (the source), how it is used (purposes), how it is shared by the candidates, and who is responsible if anything goes wrong.

However, despite requirements to be clear, comprehensive and easily accessible, everyone who has come across one knows these are too often frustratingly technical or vague documents filled with jargon. Often, they are found at the bottom of websites or prompted to users when signing up for services.

But to know how your data is being used, to hold those using it accountable, and to protect against the subversion of democracy itself, they are a crucial reference point.

In the course of the UK’s data protection regulator’s investigation into data analytics and political campaigning, the Information Commissioner’s Office (ICO) identified that all political parties use third-party data. It defines this as data:

…which places an individual in a particular segment/category, based on lifestyle-type information (e.g. what newspaper an individual reads, where they shop etc.) and is then used to make assumptions about their preferences and opinions. This data will be obtained from a number of sources – for example, from companies providing marketing data services (such as Experian or CACI), from data platforms (such as the widely used NationBuilder), or from people who have connected via a party’s social media presence.

From a cursory examination of each of the candidates’ privacy policies, Privacy International has identified two main types of such third-party data being used and which is of concern.

Campaigning Platforms

The ICO has identified campaigning platforms as third party services which campaigners use to “host data and enable political engagement”.

One of the most high profile, and used by a wide range of political parties and campaigns - including during Brexit and by Donald Trump’s campaign - is US-based NationBuilder.

Four of the six remaining candidates for Conservative party leadership have campaign sites built by Nationbuilder. These four also use cookies - software which identifies and tracks your online behaviour - from NationBuilder.

While Rory Stewart’s policy states the campaign may share data with sites “such as Nation Builder”, and Boris Johnson’s states that the campaign shares data with NationBuider for “website, email and supporter management”, none of the policies of the candidates are explicitly clear on how and for what purpose personal data is shared with NationBuilder.

At a basic level, software services sold by NationBuilder allow users to do things like manage membership lists, send updates, and track engagement. But the service also sells more advanced capabilities, allowing users to, for example, identify people’s social media activity and contacts through their email address – a service which has been disabled in France due to its incompatibility with data protection regulations.

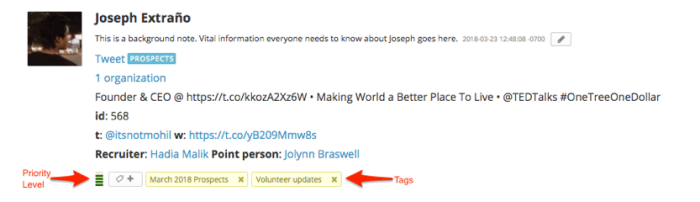

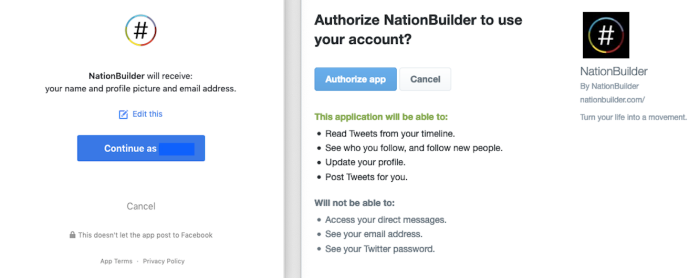

As outlined in NationBuilder’s online guides, once an email is provided to a candidate using NationBuilder, the application will automatically create a new profile for that user in the software platform used by the campaign, and match the address to the person’s Facebook, Twitter, and Linkedin accounts.

If a supporter signs up using Facebook and Twitter credentials, a new profile will also be created. Using Facebook to sign up a candidate’s campaign, for example, means allowing NationBuilder to receive your name, profile picture and email address. Once NationBuilder receives that basic data and a profile is created, various data sets can then be assigned and mapped: for example, background notes and tags can be added to the profile, as well as any location and relationship data that may be listed on your social media profile – for example partners, family members, or organisation which they belong to. Using this data, NationBuilder allows campaigns to do things like target particularly valuable profiles with specific communication, or rank their social capital ‘score’ based on their level of engagement.

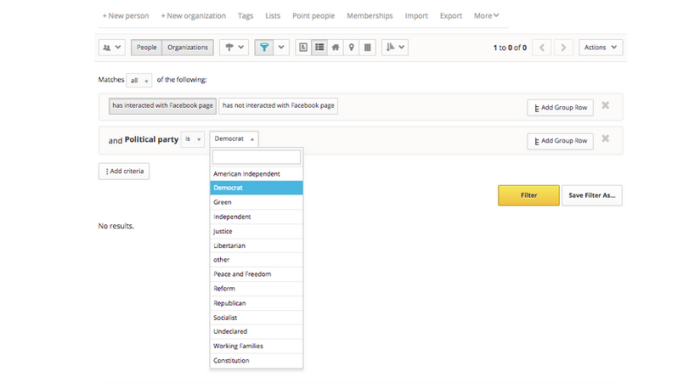

The platform then also allows users (i.e. a political campaign or those working for them) to integrate their profiles with social media data to target specific people, based on for example their location and declared political beliefs (NationBuilder uses the example of US political categories), and do things like identify and ‘tag’ everyone who has ‘liked’ a particular post.

At present, Michael Gove’s policy states that his campaign may collect, store and use data from “advocacy actions you may take part in”, including instances where people “’follow, ‘like’ or otherwise link your social media accounts to the campaign via a third-party website.” Jeremy Hunt’s states that his campaign collects “information about the services you use and how you use them, for instance when you [interact with] social media content”.

However, none of the candidates are sufficiently clear about what NationBuilder services they use, and in what ways.

The UK data protection regulator has stated that it is “concerned about the functions which allow political parties to match data from their databases with social media data from public profiles” and that the use of these campaigning platforms “should be assessed in a Data Protection Impact Assessment.” As well as carrying out these assessments, a positive step would be for political campaigns to make them publicly accessible.

Data brokers

In addition to campaigning platforms such as NationBuilder, modern campaigns increasingly use data traded by firms known as data brokers. These companies sell vast amounts of data acquired from public and commercial sources: in 2018, one such company, Acxiom, claimed to be able to provide information on up to 10,000 attributes on some 2.5 billion consumers, including on religion, socioeconomic status, relationship status, housing situation, and internet habits. For example, Acxiom segments were used together with Facebook data as part of the Conservative party campaign in the 2015 general election.

Privacy International has previously complained about Acxiom’s data processing, including profiling activities, while the UK’s data protection authority issued an Assessment Notice to Acxiom in November 2018 allowing it to investigate the company’s practices.

Gove and Stewart’s campaigns, for example, state that in addition to collecting data on “social media platforms, where you have made the information public, or you have made the information available in a social media forum run by the […] campaign”, data is collected:

- Indirectly from publicly accessible sources or other public records

- From commercial organisations with whom we have a contract guaranteeing full data protection compliance.

Much of this data is inferred, meaning it is based on profiling. Profiling is the use of data to predict more information about you: in this way, seemingly innocuous data can be used to infer extremely sensitive data, including our political opinions.

Gove’s and Stewart’s campaigns have language which mimics that of the Conservative’s Party’s main privacy policy which states that they use “the data that we collect about you in order to build a picture of you”:

We use automated means to analyse this variety of data and collate it (sometimes referred to as “profiling”). For example we may combine electoral register data, commercially available modelled consumer data and publicly available data from the land registry in order to make a prediction about your lifestyle and habits. We do this in order to:

- understand the matters and issues that are likely to be of relevance and significance to you and better inform our future policies if our predictions are incorrect,

- decide whether we send you our campaigning materials,

- select what campaigning material we send to you and which messages we put on it,

- evaluate whether we think you are likely to vote and for whom you will likely vote for during an election or a referendum,

Data might also end up back in the hands of data brokers and other companies which sell data for advertising purposes: for example, Dominic Rabb’s policy acknowledges that sometimes data will be shared with third parties for advertising purposes.

These candidates and the Conservative Party are not alone, in such practices and all political parties have recently been subject to an audit by the UK data protection regulator, the Information Commissioner (“ICO”).

Need for regulation – and for people to read privacy policies!

As highlighted by the ICO and in examples from around the world, political campaigns collecting, processing and sharing data have become common place, despite increasing concern about its impact on people’s privacy as well as on democratic processes.

For its part, the ICO has reported extensively on such risks, and is currently working on a Code of Practice for Political Campaigning. Privacy International believes this needs to address some of loopholes in the current regulatory regime: for example, despite concerns raised by Privacy International and others during the passage of the UK’s most recent data protection legislation, UK law still permits political parties to process personal data “revealing political opinions” without the need for consent. Without a highly restrictive interpretation, such an exemption allows political parties to exploit people’s data – including through third parties.

Privacy International will continue to work to challenge such political data exploitation at a policy level, including through the promotion of strong data protection laws.

In the meantime, there are things everyone can do to better protect themselves and others - as outlined in Privacy International’s guide. For a start, they can read privacy policies and put pressure on candidates and parties who rely on their support to make sure that they take them seriously. People can take very basic steps to limit the amount of data they share with third parties by limiting targeted advertising. And they can exercise their rights under data protection legislation to find out how parties and candidates use their data.

While regulatory and legislative changes are urgently needed to ensure party, local, and national democracy is not undermined by emerging data-driven campaigning techniques, in the long term this can only be achieved by the most effective check on power any democracy has – an informed and engaged electorate.

Video: Is your vote for sale? Political advertisers think so

Watch our video primer (1m54s) on how political advertisers use highly detailed data about you to target political adverts at you.