Identity Policies: The Clash Between Democracy and Biometrics

To celebrate International Data Privacy Day (28 January), PI and its International Network have shared a full week of stories and research, exploring how countries are addressing data governance in light of innovations in technology and policy, and implications for the security and privacy of individuals.

According to the World Bank, identity “provides a foundation for other rights and gives a voice to the voiceless”. The UN Deputy Secretary-General has called it a tool for “advancing legal and political rights”.

Yet, if identification is such a boon, we would expect to see the democratic process interrogating the system, giving individuals and communities the opportunity to be consulted and to fully highlight the issues, and that the kinks would be ironed out before implementation.

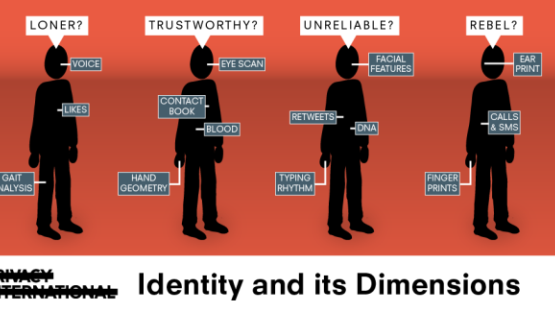

But, as the work conducted by Privacy International and its international partners show, this is not the case. We see identity systems pushed through by decree, diktat, or through means that allow less democratic accountability, denying the systems a mandate. We see the uses of biometrics expand beyond their original purpose, being used for purposes and contexts beyond their original uses. We can see the private sector, too, using these systems to link together pieces of identity, to learn more and more about people’s lives.

In many cases, identity systems are not a tool for protecting rights: they are a means by which the powerful exercise their control, often over vulnerable or under-served population.

Democracy and Biometrics In Argentina

Identity systems, particularly national identity systems, are often introduced without the firm and rigorous debate that such a major measure deserves. For example, consider the case of the Federal Biometric Identification System for Security (SIBIOS) in Argentina, introduced in 2011. SIBIOS is a database that contains the biometric details (in this case, fingerprints, palm prints, and photographs) of much of Argentina’s population. As outlined in the decree that established the system, the goal of this system is public security and crime prevention.

However, despite SIBIOS being a major project with serious implications for privacy in Argentina, it was not introduced through a debate in congress. Rather, this was introduced by decree 1766. By introducing it in this manner, essential debate on the issues was bypassed. With the decree only vaguely highlighting the goals and need for such a system — the “essential protection of the right to security” — it becomes impossible to both understand the need for such a system, as well as evaluate its effectiveness.

As our partners from the Asociación por los Derechos Civiles (ADC) argue, “the decree seems to be based on the logic of identifying individuals effectively and easily through biometric technology, not because it is the best solution for the concrete security need, but because it is available. When the legislative debate is bypassed, one loses perspective about the safeguards that must be in place to guarantee the exercise of human rights.”

Read: The Identity we Can’t Change

Updated: State of Privacy Argentina

Function Creep: NADRA In Pakistan

Concerns about identity systems are multiplied by the tendency of “function creep”: identity systems being used for more and more uses, beyond their originally-stated goals and purpose. An example of this is the system maintained by the National Database and Registration Authority (NADRA) in Pakistan, a further example of a biometric system being introduced without a debate over its efficacy.

The NADRA database contains fingerprints and photos for facial recognition. The ordinance that codified NADRA in 2000, at a time when Pakistan was under military rule, was to establish “an improved and modernized system of registration in the country”. As analysed in an upcoming publication by our partner Bytes for All, the establishment of this database risks the erosion of the right to privacy.

The uses of this database have expanded more and more. In 2014, NADRA’s database was linked to SIM card registration, which is of dubious value in fighting terrorism. Similarly, having a database of photographs, like with NADRA, leads the way to facial recognition systems: indeed, this is the case with the Safe Cities project. This is an initiative in several major cities in Pakistan that employs high-resolution CCTV cameras, making use of the NADRA database combined with the tracking of GPS and SIM/IMEI data.

As these systems become utilised in new and different ways, and as the tools and power to analyse biometrics are enhanced, then the data collected can be used for many new and intrusive purposes. When the initial data collection is conducted without a legal framework that can address potential future abuses, this behaviour by the state can continue unabated.

Identity and the Private Sector

It is not only the public sector in which this function creep occurs: the private sector, too, can embrace the power of an identity database. For example, the Indian Aadhaar biometric database of 1.3 billion people has not only been a source of increasing function creep in the public sector; it also has an increasing role in the private sector as well. Aadhaar is now used for an increasing amount of purposes, from dating sites through to the financial services sector. Nowadays almost everything is linked to an individual’s Aadhaar number.

In the financial sector, this means that more and more sources of data are used to make decisions on issues like credit scoring. This leads to the construction of a financial identity, that is then used to judge the individual’s worthiness for financial services. Privacy International recently published a report on this sector, based on fieldwork not only in India but also Kenya.

As Nandan Nilekani, former chairman of the Unique Identification Authority of India wrote, “as data becomes the new currency, financial institutions will be willing to forego transaction fees to get rich digital information on their customers.” Much of that data links back to the single Aadhaar number, enabling private enterprises to link together multiple data sources to build a more detailed picture of people’s lives. Just as identity systems enable the state to know more about our lives, so too must we be cautious about their use in the private sector.

Updated: State of Privacy India

Conclusion

While states’ implementation of identity systems varies across the world, we can see emerging themes: identity systems introduced without a proper democratic process, expanding in scope in both in the public and private sectors. For something as intrinsically personal as identity, and with identity systems so open to potential abuse, the lack of democratic debate and accountability is concerning. Identity systems are claimed to be a useful a tool for security, and are an empowering tool for citizens to make claims from the state. But, rather than empowering people and making them safer, a lack of accountability and control means that they become disempowering.