Surveillance And The City: Turning Urban Centres Into A Panopticon

To celebrate Data Privacy Week, we spent the week discussing privacy and issues related to control, data protection, surveillance, and identity. Join the conversation on Twitter using #dataprivacyweek.

Do you live in a “smart city”? Chances are, you probably do (or at least your city claims to be). But do you know what exactly makes your city “smart”, beyond the marketing term? And what does this have to do with privacy?

Companies and governments will tell you that the more cameras, sensors and connected devices it has, your city will become more efficient, sustainable and secure. After all, what commuter would complain about an app that gives them real-time information on traffic management or rideshare options? And aren’t “innovations” such as smart metres a good thing, when they can tell you how much energy you consume and when you consume it?

It’s not as clear-cut as they would have you believe. Our cities are increasingly transforming into monitored spaces, where an individual’s ability to be anonymous is steadily shrinking. On top of that, smart city projects have been used as pretexts to normalise and consolidate the systematic generation and collection of data. This is done both by governments and the private sector, ostensibly for the benefit of citizens.

The right to privacy is entirely re-defined in a (smart) surveilled city. People are no longer expected to consent to the generating, collecting, processing, and sharing of their data, but instead, are exposed to both government and corporate surveillance from the moment they leave their homes. By 2050, it is estimated that 66% of the world’s population will live in urban areas. As more and more devices are built to track peoples’ activities and to generate intelligence for use by public and private actors, this will have detrimental consequences for our democracies.

The opportunity to decide what our cities look like, and who they serve, is being taken away from us. If smart cities are to be truly democratic and inclusive, then citizens must be brought to the decision-making tables, so their diverse needs and priorities can be taken into account.

Instead of trying to solve everything with technology because it looks convenient, governments and city planners must prioritise ways to improve our cities that do not negatively affect our right to privacy in the name of unclear outcomes. When data collection is deemed mandatory, only the data that is strictly necessary should be generated and collected. Data should not be sold for commercial purposes, and citizens should be made aware of the data that is generated and collected about them and how it will be used. They should also be entitled to have it corrected and deleted.

Our work and the research of our partners in Argentina, Brazil, Chile, and South Africa, illustrate how city surveillance initiatives have been increasingly used by governments and companies to push their own agendas, while encroaching on people’s rights to privacy and autonomy, and ignoring issues of discrimination and exclusion.

Smart Cities: Better For Whom?

Privacy International recently released a report on smart cities, examining the reality of the market and existing initiatives. The research also considers the consequences and significant concerns emerging in terms of privacy and other fundamental human rights.

It finds that, in general, smart city projects are being designed and implemented based on little or no evidence, and without civilian and expert consultation. It also highlights how the current smart city narrative has reinforced problematic social patterns of inequality and marginalisation.

Read report: Smart Cities: Utopian Vision, Dystopian Reality

Recently translated: Ciudades inteligentes: Visión Utópica, Realidad Distópica

Brazil: Where Mega-Events Means “Mega” Surveillance

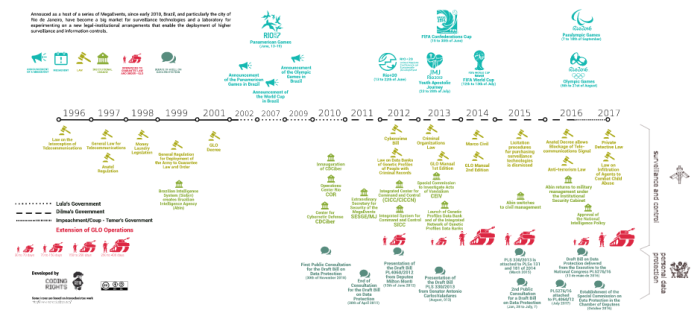

One of our partners in Brazil, Coding Rights, conducted research on how the proliferation of mega-events in Brazil, particularly in Rio de Janeiro (2007 Pan-American Games, 2013 Confederations Cup, 2014 World Cup, and 2016 Olympics), led to the expansion of the country’s surveillance framework.

Their study draws attention to the tangible changes in the capacity of the state to implement different forms of information control and maps the legal-institutional arrangements and new actors that have enhanced surveillance capabilities in Brazil since the announcement of the Pan-American Games.

Chile and Argentina: Not Your Friendly Neighbourhood Drones

Research by Datos Protegidos, one of our partners in Chile, provides a comparative analysis of the legal frameworks and uses of drones in Argentina, Brazil, and Chile. It analyses the drone industry from an economic, sociological and legal perspective, to understand the logic behind their use as surveillance mechanisms, and to identify the consequences of their widespread and indiscriminate use.

Their report shows that the drone industry is on the rise in Latin America and underscores the need for robust and comprehensive regulation to ensure human rights are respected.

Similarly, a report from Asociación por los Derechos Civiles, our partner in Argentina, explored the use of unmanned aerial vehicles by the military and security forces in that country, reviewing different cases at a national, federal and municipal level.

Read report: Drones in Chile: An Analysis of Discourses, Industry and Human Rights

Spanish version: Drones en Chile: Un Análisis de Los Discursos, Industria y Los Derechos Humanos

Read report: Alto en el cielo (Spanish)

South Africa: Overlooking the Privacy of 4 Million People

Our partner in South Africa, the Right2Know Campaign, commissioned an academic paper on smart city initiatives in Cape Town aimed at countering crime and ensuring public safety, exploring the implications of these initiatives for governance and privacy.

The research cautions authorities to be wary of developing unrealistic expectations of smart technologies as panaceas to solve systemic problems and recommends that they implement evidence-based approaches, underpinned by a legislative and regulatory framework, to ensure the right to privacy is upheld and oversight mechanisms are enforced.

Read article: Cape Town as a Smart and Safe City

Updated: State of Privacy South Africa

Conclusion

There must be a total change in the way smart city projects are implemented, to ensure that citizens are empowered to enjoy their full spectrum of rights. They also shed a necessary light over the introduction of new surveillance technologies, such as drones or balloons, their impact that they have on the inhabitants of a city.

A common thread across the study of these issues is the contempt that public authorities show regarding the impact that smart cities and surveillance technologies have on privacy and other human rights.

For further information on the State of Privacy across the world, we invite you to refer to the collaborative research project produced by the Privacy International Network.